CBC Diversity: Industry Q&A with Author-Illustrator Don Tate

When you were a child or young adult, what book first opened your eyes to the diversity of the world?

I didn’t read books as much as I should have. I struggled with comprehension and retention. There was plenty of Dr. Seuss and Mother Goose around the house, but I preferred our Funk & Wagnalls Young Students Encyclopedias. That’s where I discovered a multicultural world.

As a child, I thought the world was white. That’s what my world looked like growing up in Des Moines, Iowa in the 1960s and 70s. White people, white books, white movies, white television, white music. Encyclopedias allowed me to see the world from another vantage point. They revealed a world made up of color — brown people of every shade. Maybe that’s why encyclopedias appealed to me so much.

What is your favorite diverse book that you read recently?

I’m a little confused about the term ‘diverse book.’ It’s one of those uncomfortable, elephant-in-the-room terms, that used to mean one thing, but has morphed into something entirely different. It’s an industry code word whose definition still evolves.

I’ve illustrated children’s books for nearly 30 years — trade and educational. When I entered the business back in the 80s, people used the word ‘diversity’ interchangeably with Black or African-American. When someone said ‘diversity,’ I knew they were talking about me. I was often hired to illustrate a text because an editor had a ‘diverse,’ ‘multicultural,’ ‘African-American’ manuscript. However when I hear the term used today, it’s more inclusive, as should be. When someone says ‘diverse,’ they could mean African-American, Hispanic, Asian, Native, LGBT, girls/women, mixed-race, physically challenged, Buddhist — or even white. A better question might be: What is a favorite book that exemplifies diversity? But even that would be a difficult question because I don’t think diversity can be about one or two books. It’s about a body of books: Heart & Soul; Diego Riveria; Dreaming Up!; Around our Way on Neighbor’s Day; Alvin Ho; Jingle Dancer. There’s so many.

If you could participate in a story time with any children’s book author or illustrator (alive or dead) who would it be?

Ezra Jack Keats. It’s funny, but until just a few years ago, I thought Ezra Jack Keats was a Black man —- ha-ha-ha! — but, honestly, I did. He had a way of portraying African-American people authentically. And he did it with soul! In order for a white artist to illustrate Black people, they need to understand our skin color, hair texture, anatomy, or the art will pop off the page as unauthentic. Or at least it will to other Black people. Ezra portrayed Black characters with dignity and pride (though some early critics said otherwise). Interestingly, he did it at a time in history when Black people weren’t portrayed much in children’s literature at all. Ezra’s stories did not focus on the character’s race, racial strife, slavery, civil rights. He told stories with universal themes that every child could relate to. The color of his character’s skin faded as one got into the story. I don’t know that anyone has been able to do that since then.

How do you introduce books featuring characters of color to parents and kids?

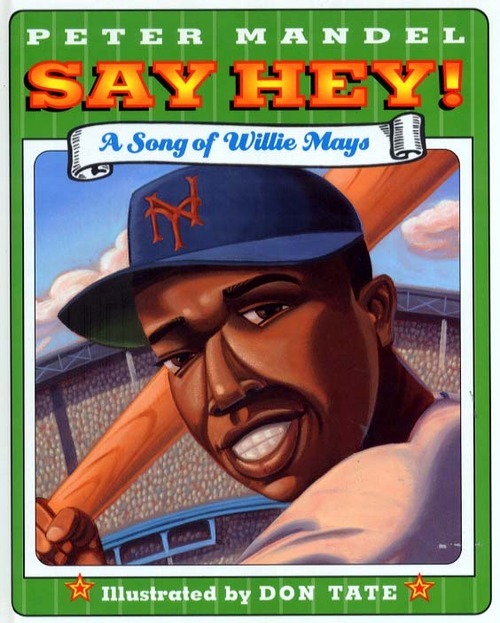

I introduce my books to kids by visiting schools and participating in book festivals. I don’t make an issue of race. I tell stories. I draw pictures. I talk about my books. My brown-face characters speak for themselves. Children, regardless of race, are open to my books. Parents, however, can hesitate sometimes. For example, one time at a book event, a white child strolled up and picked up one of my books. He was with his parents, who looked a bit uncomfortable with the situation. He turned to his mother and said, “I want this one,” pointing to my Willie Mays book. His mother smiled in attempt to hide a struggle going on inside her head. But soon her feelings were plastered all over her face: She did not want to buy my book for her kid. After a few seconds of hem-hawing, she responded, “What about one of those books?” She pointed to another author who was signing nearby. Then she pointed to another. Those authors were white. I don’t remember the authors or their books, but they didn’t feature Black characters. To my amusement, the kid did not give up. “I want this book,” he said. I fought off a smile. This has happened more than a few times. I think the more kids— and parents of all races — are exposed to racial diversity in books, the less race becomes an issue.

Authenticity is, of course, key in multicultural literature, and often times reviewers tend to highlight perceived inaccuracies. How do you think this affects the publishing industry’s decision-making process in including or excluding characters and books with diverse and/or multicultural themes?

It’s been my experience as a picture book illustrator, that when an editor has a book with African-American subject matter, written by a white author, they’ll bring on a black artist, if possible. They do this, I’ve been told many times, figuring a Black artist will bring a greater sense of authenticity to the story. I agree and disagree. As a Black artist, I know my people, culture, life experience. I can make it real. But so can an artist of another race, if they do their research like they should — Ezra Jack Keats, again, a good example.

The practice of matching a Black author to a manuscript with Black subject matter creates a niche for Black artists. Filling that niche keeps manuscripts coming our way, as long as the artwork is quality and deadlines are met. On the flip side, it can also put us into a box. I love illustrating books about my people. I am thankful to the editors and art directors who provide me work. But where are the offers to illustrate a manuscript with a white protagonist? Will that come along? Or what about a manuscript featuring a cute dog, funny pig, or crazed-out carrot? I can do a crazed-out carrot.

How can we reconcile the prevalence in reviews of readers wanting to like or sympathize with the protagonist, and our call to write people with whom they fundamentally differ?

I don’t know if the publishing industry can reconcile with readers (white readers?) who are less interested in books with protagonists who differ from them. It’s a free country, you can’t force ‘em to read what they don’t want to read. But I think if you can reach their children, you can affect the future.

When children are raised with books featuring multicultural characters, protagonist who are different from them are no big deal. As a Black male, I didn’t very often have the choice between a protagonist who looked or didn’t look like me. If I was going to read a book, it would likely feature a white protagonist. Period, like it or not. So today I can read a book like The Marbury Lens and not get tripped up on the race of the character.

As someone who reads, loves, and often reviews children’s literature, please provide what you feel are the three most important things to keep in mind when writing a diverse character or about a different culture.

Be wary of stereotypes. Check your work by checking with others. I belong to several writing critique groups. I’m the only person of color within those groups. When my friends write about other races, I’m careful to point out stereotypes or things that might be offensive to people of color. My friends aren’t racists in the least bit, but they’re human. They have preferences and biases, same as I do. But they’ve probably never been the victim of racism, and so they just don’t know when the line has been crossed.

The question of stereotyping can be fine line to walk, in my opinion. Lets say a white author writes a story about a Black teen, who lives in an urban neighborhood and likes to play basketball, is raised by a single mother, whose father is dead or in prison. Is this stereotypical? Yes, kinda. But is it realistic? Oh, yes! Should a white author avoid this kind of imagery for fear of being called out on stereotyping? No, I don’t think so. But I advise that they check themselves by checking with Black people. And if they don’t know any Black people, well, there’s where the problem will begin.

If more books were published like Varian Johnson’s My Life As A Rhombus, books featuring suburban, Black math-whiz teenagers, in homes with two caring and hardworking parents, the other stuff wouldn’t likely be an issue anyway. Balance is what’s needed.

Don Tate has illustrated many books for children, including She Loved Baseball, Ron’s Big Mission, Duke Ellington’s Nutcracker Suite. He is also the debut author of the award-winning It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started To Draw. Don lives in Austin, Texas.