CBC Diversity: First, Know Yourself

“Write about picking cotton,” my family said when they heard I wanted to be a writer. “Write about how we used the fabric from flour sacks to make our dresses, and how Grandma hates fish because that’s all she ate during the Depression, since it didn’t cost anything for them to go fishing for food.”

Closely examine my family, or any family, and you’ll discover all the drama of a telenovela. Naturally, I wanted to write about being chastised for speaking Spanish, about living on a ranch in San Diego, about my grandmother being “Rosita the Riveter” during World War II. I tried to write those stories. But my only experience working the land comes from fifteen minutes in a field off Old Robstown Road where my parents showed us how to pick cotton. It was interesting to feel the texture, so unlike a T-shirt, which is what I had imagined.

My grandmother might have hated fish, but I loved it. We had a boat that we’d take to Laguna Madre, where we’d compete to see who could catch the most, the biggest, or the strangest. (Once, my brother caught a seagull when it chomped on the bait as he cast.) Back home, Dad filleted the fish in the backyard, the cats begging and fighting over scraps. Then, Mom used cornmeal batter to fry the fish, and we ate, delicately picking meat off tiny bones.

All this to say that my family’s experiences and the emotions associated with them are not exactly mine.

So what do I know about writing from an authentic Mexican American perspective? Of course, I do write from that perspective because that’s who I am, but one of the struggles I’ve faced is matching the expectations of two groups of readers—brown and white. Interestingly, both often expect stories about characters who are recent immigrants, who speak Spanish, who are gardeners, maids, or nannies, and when I write stories about people who fall outside these categories, they are judged as “too mainstream” or “not Mexican enough.”

While writing about the “authentic” Latino experience is important, I fear that sometimes other, equally authentic stories get overlooked. For me, these are the stories inspired by my own childhood and by the experiences of my students and sobrinos. Like me, they don’t know what it’s like to work in a field, to go hungry, to use the fabric from flour sacks to make their dresses. Like me, they don’t know what it’s like to speak Spanish beyond a few phrases, and they feel saddened by the inability to have deep conversations with their Spanish-only grandparents but also proud to be fluent, even persuasive, in the English they hear at school, in the neighborhood, on TV.

I used to worry that I wasn’t fulfilling my obligation to write what would be unquestionably categorized as Mexican American literature. But then I had this insight. The Latinos in this country are wonderfully diverse. They come from Mexico, Cuba, and Columbia; they come from San Antonio, Los Angeles, and Winston-Salem. They are gardeners, maids, nannies, dentists, engineers, and mayors.

For those aspiring writers out there, accept that your experience may not fit neatly into a category because in order to write an authentic story, you must first understand and be true to yourself.

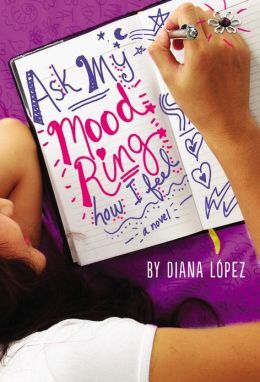

Diana López, author of Confetti Girl, Choke, and Ask My Mood Ring How I Feel.