CBC Diversity 101: The Disabled Saint

A Caricature, Not a Compliment

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Kayla Whaley

It’s difficult to find any representations of disabled characters in any form of media. In GLAAD’s annual look at minority representation on scripted network shows, there were only eight characters with disabilities in the 2013-2014 season. That means of all the characters on network shows in primetime, a whopping 1% had a disability.

That figure measures only a very small segment of the media, but it is indicative of a larger problem: the woeful lack of representation of people with disabilities across the board. I would argue that this dearth of disabled characters makes it even more important that the ones we do get are respectful and thoughtful portrayals.

I would also argue that those characters that aren’t—those that perpetuate harmful stereotypes, clichés, and tropes—are even more dangerous than they otherwise would be given that lack.

Personal Connection

I was born with a degenerative neuromuscular disease, and have used a power wheelchair since I was two. I can distinctly remember the first time I saw a character that used a wheelchair. I was ten. I just want to emphasize that I didn’t see a single character like me for the first decade of my life. It didn’t even occur to me to ask for a wheelchair-using character.

But then there one was. Here was a movie where someone like me would not only be a character, but the main character. I was ecstatic. Until I actually watched it, and then I couldn’t figure out why I felt so utterly disappointed, almost betrayed. I didn’t understand that feeling then, but I understand it now.

Description of Clichés/Tropes/Errors/Stereotypes

Perhaps my most hated trope having to do with disabled characters (and this one tends to happen most often to physically disabled characters, though not exclusively), is that of the “disabled saint”—the good little cripple, perfect in personality in spite of being wholly imperfect physically.

Innocent and pure and forever denied their humanity.

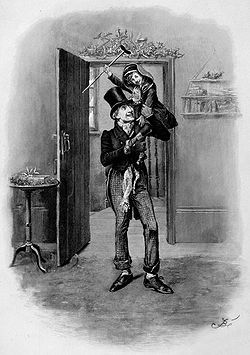

The classic example is Tiny Tim, though this trope exists everywhere. The movie I mentioned above was a Disney Channel original called Miracle in Lane 2. It tells the story of a boy who uses a wheelchair and begins soapbox racing. It’s been many, many years since I’ve seen it, but I distinctly remember being uncomfortable. I realize now it’s because the character wasn’t a character; he existed solely to inspire both the audience and the other characters, otherwise known as inspiration porn. The disabled saint trope is a specific (and very common) form of inspiration porn. But it’s important to note that while all “disabled saints” are necessarily inspiration porn, not all inspiration porn necessarily involves a “disabled saint.”

I want to be clear: disabled characters (and disabled people) can certainly be inspiring, but they are not inspiring simply because they exist while also having a disability. All forms of inspiration porn, including the “disabled saint” trope, tell the abled audience that people with disabilities exist to make them feel inspired. It removes the focus from the disabled characters, and turns them into props that exist entirely to impact the abled characters and audience.

The “disabled saint” trope is particularly insidious because it tells the audience that disabled people are and should be perfect in spite of (or maybe because of) their disabilities. It places an utterly impossible standard on actual people with disabilities. Because no one is perfect. No one is innocent or pure (whatever those words even mean), and expecting any and all disabled people to exhibit those qualities sets them up for “failure” when they turn out to be humans and not saints.

Representation matters, and when the only disabled characters shown are saints and inspirations, how does that impact actual people with disabilities? I can tell you how it impacted me. I can tell you how I’ve been told time and time again how “brave” and “courageous” I am for simply existing while using a wheelchair. I can tell you how almost every public acknowledgement of my accomplishments has come with a statement of how “she never lets her disability stop her/get her down/change her.”

I can tell you how important it felt to be the best in school. To be liked. To be funny. To be sweet and smart and perfect. Because I felt that I had to prove myself.

I can tell you how one time my dad told me he thought anyone born with a disability was also born with some exceptional quality to make up for it. I can tell you how I nodded along and tried to figure out what my special quality was that justified me existing, though I didn’t have the understanding or language to know that’s what I was doing.

I can tell you that representation matters. That there are no saints in this world. That neither I nor any disabled person exists to be an inspiration.

What I’d Like to See

I’m honestly not sure where I stand on the “no representation is better than bad representation” debate. But I do know I want to see a) more representation of disabled characters, and b) better representations, including fewer “disabled saints” (read: no more ever). I encourage you to add disabled characters to your stories, but I also encourage you to question your preconceptions, to research, to talk with disabled people. Ultimately, it all comes down to being intentional and respectful.

Don’t deny your characters—any of your characters—their humanity.

Kayla Whaley is a co-moderator of Disability in Kidlit, a freelance editor, a YA writer, and a fervent supporter of diversity in kidlit (and all lit).