CBC Diversity: “Here I Am!”

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Brian Pinkney

When I was ten years old, my mom and dad made me my very own art studio. Actually, the “studio” was a walk-in closet that my parents converted so that I could have a place to call my own. It was the perfect spot for expressing my creativity without interruptions. (As one of four children, finding time to myself wasn’t always easy.)

As a budding artist, I wanted to grow up to become a children’s book creator, just like my father, illustrator Jerry Pinkney. Watching Dad, I was very fortunate to see books in which black children were front-and-center. Seeing Dad’s characters showed me, me. And it established a simple truth ― black kids in books were beautiful and could be rendered abundantly.

Following in Dad’s footsteps, I spent hours in my little workspace drawing all kinds of pictures. I also read lots of books, and dreamed big. Looking back, I realize now that my junior studio was a kind of retreat where I could pore over the pages of picture books. These books and their illustrations had an impact on how I perceived myself as an African American kid.

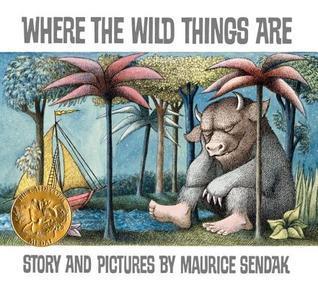

I also escaped to the studio so that I could enjoy all kinds of adventures that bubbled up in my imagination as I wrapped myself in books such as Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. It didn’t matter to me that Max, the kid in Where the Wild Things Are, wasn’t black. He was me, and I was him. I saw myself through his adventures, not through his skin color.

Also, having observed my father’s depictions of black children, while at the same time loving books with all kinds of characters, gave me the gift of seeing picture books through two lenses ― the experiential and the cultural.

With so few picture books that included black characters like Max in Where the Wild Things Are ― kids who were having fun, embarking on adventures, pushing past authority, and exploring unchartered forests ― I was made to straddle two worlds: the universe of just being a kid and the land of being a black boy. Because I saw so few black kids in picture books who were like Max (and, who, through their adventures, were like me too), I was plunged into a syndrome that I’ve come to call “Where Am I?”

It’s been said many times, but can’t be stressed enough. Here’s how “Where Am I?” manifested in my world:

- As an African American kid growing up in the 1960s, there were very few books that reflected my experience.

- There weren’t many books that depicted boys who looked like me embarking on new discoveries, in the same way Sendak’s Max had done.

- By not seeing myself represented in books in these ways, I began to feel like a nonentity ― like the hole in the doughnut. I constantly asked, “Where am I?”

Seeing my father’s work showed me that, like my Dad, I could be the one who could someday give black kids images of themselves in books that reflected universal experiences. As a fourth grader, I didn’t walk around pounding my chest claiming to change the world through my art. Instead, I made a quiet, conscious choice. And as I grew as an illustrator, I stepped into that choice by deciding that the books I wrote and illustrated would do more than simply depict kids of color. I set an intention. Through my picture books, I would change “Where Am I?” to “Here I Am!”

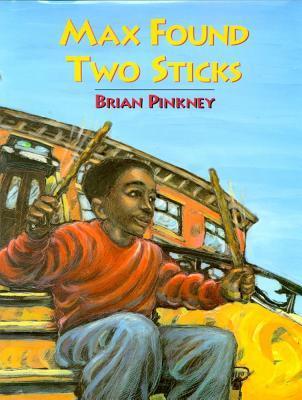

I started with a Max of my own creation. In my debut book as an author/illustrator, entitled Max Found Two Sticks (Simon & Schuster), young Max has limited language ability. Instead of talking, he expresses himself through the drumbeats he plays on the objects found in his urban neighborhood. Through Max’s own musicality and kinetic intelligence, he expresses his creativity and brilliance to everyone he meets. There’s also a magical realism element to the story. Not once is there mention of Max’s racial identity or ethnicity. He’s any kid and every kid who discovers his power through his own unique form of self-expression.

Max Found Two Sticks is one of my best-selling titles to date, and it has been embraced by kids and parents for its ability to empower readers of all types and abilities ― kids who struggle with reading and language; kids who are creative; children on the autism spectrum; and those who perceive their world through sound.

Max Found Two Sticks showed me something important, as it relates to diversity. I discovered that by empowering black characters, I was empowering all kids. This would seem obvious, but to many, it’s not. There’s still an assumption that picture books with black kids (especially black boys) as their central characters, can only appeal to a limited segment of the population. That showing a black boy front-and-center on a picture book’s cover, means that book is “for black boys only.”

It was an uphill climb to gain “crossover success” for Max Found Two Sticks. But it happened after years of me presenting the book at school visits and literacy conferences, where young readers and adults began to look past the book’s cover to its universality.

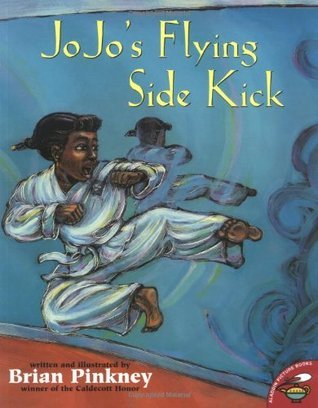

The same has been true of a picture book that I wrote and illustrated, entitled Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick (Simon & Schuster) about a girl who finds her own inner strength when she aces a martial arts test. The book’s cover shows high-flying Jo-Jo, who is African American, performing her best Tae Kwon Do maneuver. My intention with Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was to take the “Here I Am!” ideal to even greater heights. But I soon learned that the book had two strikes against it, in the eyes of some readers. People assumed that Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was a book for either Asian kids or black kids only ― until they read it, and saw that, like every child, everywhere, Jo-Jo faces, and overcomes, some of her worst fears. For reasons similar to Max Found Two Sticks (the limited perceptions of viewers who choose books by cover images), Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was a slow build. But in time, the book turned into one of my strongest sellers, often purchased by parents, kids and teachers who are not of color.

I’m now embarking on a new book, entitled On the Ball (Hyperion/Disney Publishing, Fall 2015) that employs some of the same elements as my previous books that I’ve both written and illustrated. The story is told in minimal text. A curious boy chases after a lost soccer ball, and finds mystical animals, as well as his own hidden talents.

As a renderer of images that affect children, it’s essential that I stick to my commitment of showing black kids in all their glory. By doing this, I hope to be able to bring power, change, healing, self-expression, and heart to children of every color.

For anyone who reads and shares picture books with children, here are some tools that are helpful in moving past “Where Am I?” ― and making “Here I Am!” the way of our world:

- Cover Conversations: Before even opening a book, engage a child in a discussion about its cover by saying, “Wow, look at that boy on the front. He’s got drumsticks in his hand. What do you think this story is about?” And then inviting the reader open the book to find out more.

- Make it Personal: Ask a kid, “What are some of the things in this story that are similar to your own life, family, school, dreams, plans, etc.?

- Teachers Teach: Insist that your child’s teacher or school librarian always, under all circumstances, include books during story times and in classroom libraries that include people of color. Most folks are well-intentioned, but sometimes forget.

- Sail Away: Let a book’s story drive a child’s interest, rather than the color of its characters. Invite kids to create their own adventures based on the book’s themes.

Brian Pinkney is a two-time recipient of the Caldecott Honor medal and a New York Times bestselling illustrator. He was named one of the “25 Most Influential People in Our Children’s Lives” by Children’s Health magazine. To learn more about Brian Pinkney, visit www.brianpinkney.net.

Brian Pinkney is a two-time recipient of the Caldecott Honor medal and a New York Times bestselling illustrator. He was named one of the “25 Most Influential People in Our Children’s Lives” by Children’s Health magazine. To learn more about Brian Pinkney, visit www.brianpinkney.net.