Month: January 2015

-

Kate DiCamillo Named National Summer Reading Champion

Washington—The Collaborative Summer Library Program (CSLP) has announced its partnership with award-winning children’s book author and National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, Kate DiCamillo, as its first ever National Summer …

-

CBC Diversity: Inclusion vs. Diversity

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Tonya Cherie Hegamin

Human brains like to compartmentalize, and I believe that the term “diversity” serves to place people in boxes marked “other”. However, as individuals, the cultural, physical and learning differences we have must harmonize for survival. I expect to be addressed as a whole human, not one whose life circumstances make me ‘different’. Truly, “diversity” in its best light seeks to celebrate our differences, to acknowledge those on the margins of “normal”, but it does not necessarily seek to include all of us as we are. Would you choose to just be tolerated or to be wholly accepted as you are?

Personally, I consider myself to be beautifully complicated. On the surface, many people might think I’m Latina or biracial because of my skin color and hair. In reality I am multi-racial, just like so many other people. Once when I was five, a neighbor (who was white) asked me “What are you?” I didn’t understand—I asked my mother and she told me to say I was “black”. When I went back to my playmate, she informed me that I couldn’t be black because I didn’t look, act or sound black, and if I was black her parents would refuse to let her play with me. That’s a lot for a five year old to handle. Not just for me, but for this girl who was subjected to a binary world where some people were “acceptable” while others were not.

For me, it was only the first of a countless number of times people demanded to know what I was. I come from a long line of ‘light skinned’ African-Americans (both my paternal grandfather and great grandfather passed for white to get jobs) who mingled with Nanticoke Indians (my maternal grandfather could trace his family to the last ‘royalty’ of the tribe), also Dutch, Haitian, Scottish and probably a hundred other combinations. Both sides of my family still hold emancipation papers from ancestors who begat the children of their masters. Internalized racism, color-isms and social/class structures probably supported my family marrying those whose experience was similar; yet we still identify as black or African-American. At this point, I’ll remind us all that “race” is a social construct created to specifically compartmentalize dark skinned people as inferior and white Europeans as superior. However, we are still hooked on creating separate compartments for people, and I believe the claim of ‘diversity’ supports that line of thinking.

But my beautifully complicated world does not hinge on race or culture alone. I also have dyscalculia (a learning disorder) and a chronic immunodeficiency disease which requires multiple daily injections and also causes chronic pain, fatigue and depression. Therefore I’m in the “disabled” compartment too. I am also bisexual, yet another compartment. Do I live in a compartmentalized body, mind and soul? Of course not. I have learned to integrate and include all of that “diversity” as a part of my singular human experience. At five, I just wanted that playmate to include me in the fun. Growing up I became severely depressed trying to prune myself to fit into one group or another; now I realize it never works, I accept myself as I am.

Teaching in a predominantly black college in Brooklyn, NY also made me realize the value of inclusivity over diversity. In my Children’s and Young Adult Literature classes, we critically examine inclusive literature and how it allows readers access to a variety of world views and perceptions. I’ve learned another hard lesson in those classrooms—I realized that I suffer from ‘perceived commonality’. I thought that because my students were also black, we shared a communal memory of racism in America. I now know that many of my students would never identify themselves as black, much less American. They are all just as beautifully complicated as me!

I stress to my future teachers to teach the individual as they are, to include a variety of perspectives. As a writer, I strive for that, too, but I also try hard to make every character as “real” as possible; for me, that means including all the contradictions and complexities that in the end, makes them beautiful.

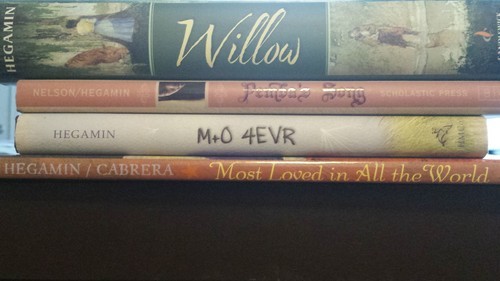

Tonya Cherie Hegamin is the author of the young adult novel Willow, M+O 4EVR and the coauthor with Marilyn Nelson of Pemba’s Song. She received an Ezra Jack Keats New Writer Award and a Christopher Award for her picture book Most Loved in All the World, illustrated by Cozbi Cabrera. She is the creative writing coordinator at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn. Learn more about Tonya by visiting her website: www.tonyacheriehegamin.com.

-

Holly Black Reveals The Influences Behind ‘The Darkest Part of the Forest’

“There are a few bits of folklore I drew on specifically for The Darkest Part of the Forest. I started with the idea that I was going to rewrite a …

-

‘It’s Possible’ Series: A Place in History

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Jennifer M. Brown

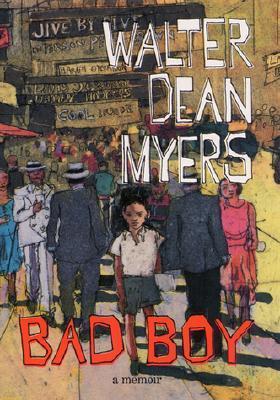

"Each of us is born with a history already in place." Those words open Walter Dean Myers’s memoir, Bad Boy. The word “history” applies to that of the individual child, born into a family and a set of circumstances. “History” is also tied to a physical place. Walter Dean Myers was profoundly aware of both.

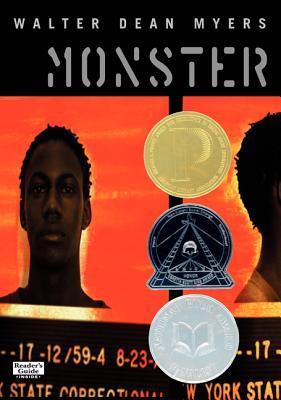

He believed that individuals could change history; he watched them do it, and he was an instrument of change himself. He also had deep ties to his childhood home in Harlem. From his picture book Harlem, illustrated by his son Christopher Myers, to his Newbery Honor book Scorpions and the inaugural Printz winner, Monster, he wrote of Harlem’s glories and its sorrows. If you were lucky enough to hear him tell stories of his youth, he’d describe walking down the street and stopping to talk with Langston Hughes, and attending dances and sermons at “a shouting church,” immortalized in one of the poems in Walter’s collection Here in Harlem.

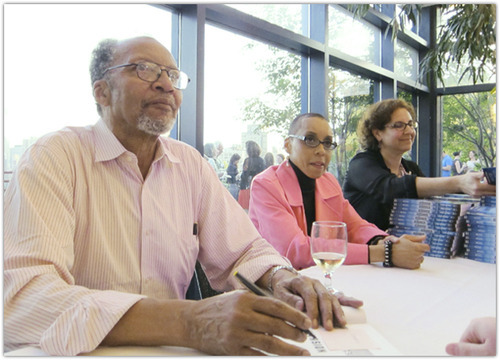

I was 21 and assistant to Bill Morris, director of library promotion at Harper & Row, when Bill introduced me to Walter. They made a comical pair. Bill, the Southern gentleman at 5’2”, and Walter, a full foot (and then some) taller and a straight-shooter New Yorker. But they were great friends, and had the utmost respect for each other. From this vantage point, I got to hear Walter speak at numerous conferences. Wherever Walter went, he commanded a room, standing head and shoulders above most of the people in it. It wasn’t always what he said that made you tilt forward, trying to eavesdrop. It was the way he listened, followed by the concise response that conveyed how closely he’d listened, sometimes responding to what you hadn’t said.

A year ago, when Walter Dean Myers, as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, passed the torch to his successor, Kate DiCamillo, he described what he called the most important moment in his two years as Ambassador: “I was in a prison that was loosely run. By that I mean, some talking is allowed among the inmates,” Walter said. When he started to speak, an inmate was talking. “‘Keep quiet, I want to hear this,’ one inmate said to the other,” Walter recalled. “That touched me. I knew this program was working.”

When Walter spoke at the 92nd Street Y, a year into his ambassadorship, he described a conversation he’d had with Langston Hughes when Walter was in his 20s. Hughes had been criticized for writing for “the lowest element of black life,” as Walter put it. Hughes told Walter, “That’s who I want to write for.” In his book Just Write: Here’s How! Walter wrote, “Reading probably saved my life.” For him, reading was not an option, it was essential. He transformed his personal credo into his platform as ambassador: “Reading is not optional.” He also says, in Just Write, “I write books for the troubled boy I once was, and for the boy who lives within me still.” He worried about the kids who begin school behind, and how only 15% of them ever catch up.

He worried about them because he’d been where they were and he’d walked in their shoes. He also wanted to give them hope—if this “bad boy” could turn his life around, so could they. He knew, too, that his stories could appeal to people who had not walked in their shoes. If Walter, as a teenager, could relate to Stephen Daedalus in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, then books could unite all races and cultures. Books could save the lives of young people everywhere, in myriad ways.

Even after he’d won the inaugural Printz Award, multiple Coretta Scott King Awards and Honors, Newbery Honors, the Virginia Hamilton Award, the Margaret Edwards Award and been named a National Book Award finalist numerous times, Walter continued to challenge himself. Soon after he’d won a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, to spend some uninterrupted time writing in a cabin in New Hampshire, he told me his goal while there was to “slow down.” He wanted to write fewer pages a day. But I don’t think he ever could. He had too much to say.

It’s hard for me to believe that Walter Dean Myers no longer walks the earth. His sense of humor, his world view, his wisdom, remain with me. Hardly a day goes by when I don’t think, What would Walter say about this? What would he notice that I’m missing? How can I pay more attention to what matters? The closing lines of Bad Boy uplift me: “Writing had let me into a world in which I am respected, where the skills I have are respected for themselves…. All in all it has been a great journey and not at all shabby for a bad boy.”

Jennifer M. Brown has been in children’s books for more than 25 years. She writes for School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, and is children’s editor of Shelf Awareness. She is also the director of the Center for Children’s Literature at the Bank Street College of Education.

-

When It Comes to Books, Allow Kids to Enjoy Freedom of Choice

“For decades, researchers have been suggesting that a little structured fun with books can help kids learn to appreciate them, and that kids who like to read tend to become …

-

Age Appropriateness & Children’s Literature

Many are in favor of allowing kids and teens to “self-police” the books they read, trusting that they can decide what material they are equipped to handle. Shielding children from potentially upsetting …

-

‘It’s Possible’ Series: “Okay, Love.”

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Virginia Anagnos

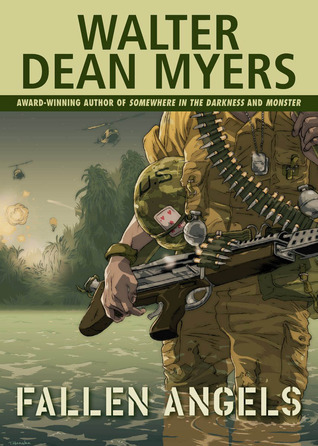

I was a publicity assistant at Scholastic Inc., when I first became aware of Walter Dean Myers’ work. The book: Fallen Angels. My perspective on children’s literature was changed forever after reading the first few pages, and by the end of the book I was in awe of the man.

I met Walter a few years later while working on Brown Angels and the photographic exhibit based on the book, which traveled across the country. My first encounter with him exemplified our ensuing relationship.

He had refused a car service to Harlem for the opening of the Brown Angels exhibit, and we agreed to take the subway together to the publisher’s dismay. Hey, it was the early ‘90s—NYC subways were not what they are today.

We were looking over the media coverage when a fight broke out among some teens. Walter immediately tried to divert my attention by insisting I read the review in Newsday again. He kept tapping the newspaper and saying, “Read here, read here!”—while looking at the group, not realizing that the paper was upside down. I smiled and said “I’m a Queens girl. I’m not rattled by a little noise. I got your back.” (Amusing visual, since I am 5 feet petite to his over 6 foot frame.)

Walter made an indelible impression on me during that campaign. He was steadfast in his conviction that children needed to recognize themselves in books like Brown Angels. They also needed to see themselves as beautiful and valued. I knew the importance of reading, but he helped me realize the power and potential impact of a children’s book on young lives. It was an idea that was expressed consistently through our work together and informed my work as a book publicist.

I was excited when years later his agent, Miriam Altshuler, approached me about working on Walter’s newest book, Shooter. I had left publishing and was (and still am) working at Goodman Media International, the PR firm. I loved working on book projects and was thrilled to be reunited with Walter.

The routine went something like this: Miriam would call and say, “Walter has a new book, would you consider working on it?”—as if there was any doubt. After reading the manuscript, I’d call Walter. We would have in-depth conversations about the story, how this latest book fit into his overall repertoire, and how we’d leverage this opportunity, as well as our previous efforts to reach kids who were on the brink of making a choice that would affect them for the rest of their lives. Of course, we also talked about the latest antics and mischief caused by his cat. But at the end of each call, any call, he would always say: “Ok, love,” and the work would begin.

The campaigns were as varied as the many formats and genres of his books. We went beyond the traditional media relations strategy—everything from pursuing school adoptions for his books, to partnering with organizations on unique-to-his-book initiatives such as “Second Chances,” to appealing to the Supreme Court Justices while they deliberated on whether to ban life sentences in some teen cases. (They did ban them!) Anything and everything to reach, protect and give voice to youth, especially those who needed it most.

Large and small victories had a compounding effect until Walter was named National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. We knew unequivocally what his platform would be: Reading is not optional. It embodied his journey and was unwavering in its stance—just like Walter Dean Myers.

The last time I saw Walter Dean he was addressing a group of foster parents when a parent asked: “Is a single parent enough to raise a child?” He replied swiftly: “Absolutely, as long as that child is loved.” I struggled to hold back my tears. As a single parent, I took great comfort in his response. Raising sons was also a topic we occasionally discussed on those long calls. I wanted to tell him what that response meant to me and thank him for his answer, but I never got the chance.

Thinking about it now, how do you thank a man whose compassion was boundless; whose tenacity to portray poor inner-city children as human in the eyes of the reader was relentless; who forged new paths with his work and for others just like him, who challenged us and inspired us to be our best selves? I know what I would say.

“Walter, we got your back. We’ll make sure your legacy lives on. Ok, love.”

Virginia Anagnos, Executive Vice President at Goodman Media International, has established and spearheaded significant initiatives and events for numerous publishing and literary clients. Prior to joining Goodman Media, Anagnos spent thirteen years in book publishing executing publicity campaigns for noted authors and historical figures.

Virginia Anagnos, Executive Vice President at Goodman Media International, has established and spearheaded significant initiatives and events for numerous publishing and literary clients. Prior to joining Goodman Media, Anagnos spent thirteen years in book publishing executing publicity campaigns for noted authors and historical figures. -

J.K. Rowling & Fan Activists Score Unprecedented Victory Against Child Slavery

Fan activism just landed a major victory. Warner Bros., the studio behind the Harry Potter movies, is moving forward with plans to make all Harry Potter chocolate sold at Warner …

-

Announcing the 2015 Sendak Fellows

This year’s recipients are: Richard Egielski Marc McChesney Doug Salati Stephen Savage The fellowship was inaugurated in 2010 by Maurice Sendak, the goal of which, in Sendak’s words, was to …

-

‘It’s Possible’ Series: Walking and Talking with Walter Dean Myers

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Regina Griffin

Whenever I think of Walter, I remember walking together. From the moment we met, we walked endlessly, tiptoeing like cartoon characters over the hot bricks of Centennial Park in Atlanta, strolling down the River Walk in San Antonio, giddy after a speech’s end, striding up steep hills in San Francisco, with Walter practically lifting me up, because my feet could not stay in the slip-on shoes I had insisted on wearing. We walked all over Chicago, listening to blues music, delighting in crowds celebrating not one, not two, but the three-peat of Bulls victories, though Walter’s heart would always remain with the Knicks of Earl “the Pearl” Monroe and “Clyde” Frazier.

We walked the long avenues of Washington, DC, sometimes in 100-degree weather, sometimes in light snow. Once we arrived after an actual blizzard hit and somehow managed to make it to Anacostia for an Open Book event. That event was made unforgettable by some struggling young dads who got there against the odds, even if it meant carrying their children through more than a foot of snow on uncleared streets and sidewalks. Walter Dean Myers was coming. They weren’t going to miss him.

Walter and I became colleagues, editor + writer, and friends during our walks. He was curious about everything, and so we spoke about anything: the best point guards, school reform, the latest Conor McPherson play, Delta versus Piedmont blues, Matisse’s book Jazz, slavery in New York State, new finds for Walter’s ephemera collection, which of us loved W.B. Yeats more, the boxers, Walt Whitman’s poems, ships of the line and how scary it must have been to be a powder monkey on them.

Our walks, our talks, led us to the beginnings of many different projects, books that ranged throughout the age levels and different genres of children’s publishing. Basketball madness—demonstrated by our stopping at the Cage (the courts on Sixth Avenue and West Fourth Street) to pay homage and critique the players—led to the signing up of Slam. Our joint interest in boxing and love of history, our admiration for people who make a difference, led to his doing a biography of Muhammad Ali, which ended with our both learning the damning truth of boxing’s costs. That same passion for history infused his work on Malcom X: By Any Means Necessary, his biography for older children. Walter felt the importance of presenting as thorough and as rich a history to kids as he could; he felt it as our duty and obligation. No more lies; no more half-truths.

Bits of different conversations, ideas, and interests would meet and challenge one another until a book was born. Early one morning, Walter and I met in the Village. As we passed by the stoop of my building, where I often sat, we discussed how images are presented, how they are framed to make a point—that a person sitting on a stoop in Harlem would be presented differently from my sitting on my stoop in the West Village. He eventually decreed that the picture set in Harlem would end up in sepia, the paper distressed.

This point, coupled with our joint admiration of the Matisse cut-outs, led to his writing a picture book that would celebrate Harlem during a difficult time in its history. Vivid, colorful images, brimming with joy and pride, would honor not only the neighborhood, but also the people who had made it what it was, and the people who lived there still. To Walter, providing an alternative narrative to the “standard” one—a strong, exhilarating riposte to the usual jeremiads of decline and danger, one that did not ignore problems, but that recognized a larger context—would prove a firm step on his mission toward change. That the final book paid more of an homage to Romare Bearden’s work than Matisse’s, as well as showcasing his son’s first picture book art, only made the journey to it more thrilling, because the evolution of a project, of a neighborhood, of a nation, can inspire awe.

Yet our discussions were not only about the next project. Those decades we spent walking through convention centers, theaters, and school auditoriums gave me an education in seeing, in putting myself in other people’s shoes. Witnessing the way Walter always introduced himself to serving staff at parties, experiencing the genuine interest he showed in every person he met, with curiosity and deep respect, even—or perhaps, especially—prisoners, challenge me to do better, both as an editor and as a citizen.

Yet it was during those walks through convention centers that he began to get discouraged. At a BEA, he said, come on with me and pointed out that the shift to more graphic, iconic images had essentially erased the progress made toward presenting covers that reflected more of our country’s people. A month later, we did the same thing at ALA, and continued to do so at every conference we attended together until his death.

Now that Walter has left us, I will no longer be able to walk all over this country chatting with him about everything, anything, and nothing at all.

But I will still be able to move in the direction he sought. I will still be able to work for social justice and a more complete representation of our country.

I’m going to call upon all of you to join me by quoting a poet Walter and I both loved:

“We must march, my darlings.”

—Walt WhitmanI won’t be walking, I’ll be marching.

Regina Griffin is an Executive Editor at Egmont USA. She was previously the Editor-in-Chief of Holiday House, and before that an editor at Scholastic Inc., where she first had the honor of publishing Walter Dean Myers.

Regina Griffin is an Executive Editor at Egmont USA. She was previously the Editor-in-Chief of Holiday House, and before that an editor at Scholastic Inc., where she first had the honor of publishing Walter Dean Myers. -

Scholastic Releases Exclusive Images from Upcoming Illustrated Edition of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone

New York, NY – Scholastic, the global children’s publishing, education and media company, today released four exclusive new images from the eagerly anticipated fully illustrated edition of J.K. Rowling’s bestselling Harry …

-

‘It’s Possible’ Series: Pushing the Envelope and Making a Difference

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Phoebe Yeh

The very first project I worked on with Walter illuminates a lot about our collaborations together. It was 1994. Walter had already received acclaim for his realistic fiction (the Newbery Honor books, Scorpions and Somewhere in the Darkness) and Now is Your Time, a work of ground-breaking non-fiction (to name a very, very few). Somehow, I had come across The Dragon Takes a Wife, a picture book Walter had written in 1972 starring Harry, a hapless dragon and Mabel Mae, a jive-talking African American fairy who tries to help Harry defeat the African American knight in shining armor. Here was another way to think about the classic medieval tale. I loved the way Walter had re-invented the traditional story and thought, we need to bring this book back. It’s a perennial storyline. It’s funny. It’s fantasy and it offers a perspective readers seemed to have forgotten, at least in the nineties. (Of course Walter had already figured this out in 1972. We obviously had some catching up to do.)

Fast forward to 1997. Now we’re collaborating on a teen novel. (I don’t tell Walter that actually, I’ve never edited a teen novel – only picture books and middle grade novels.) He shows me a copy of the screenplay Harold and Maude, a street purchase. I have reservations about a screenplay but Harold and Maude is one of my all-time favorite movies. Maybe it’s going to be all right. Of course no one has ever attempted anything like this before for teens. But it’s so intriguing and innovative. And Walter is so convincing about why the screenplay format is the right way to go for his new book. There will also be journal entries and interior art, using multiple formats and perspectives to tell the story about Steve Harmon, who is in jail for felony murder. I could write many, many blogs about what it was like to work with Walter on shaping and refining Monster, truly revolutionary for its time. This is when I learned that Walter was one of the best writers of dialogue in the business. That problem-solving was a challenge he welcomed. That he would leave no stone unturned to get it right because he wanted his readers to read the best book he could write for them. That he didn’t shy away from “controversy” by showing an African American boy on the cover of a book called Monster. That was the point. Some people thought about Steve this way. Steve knows he’s not a monster. But he’s gotten himself into a situation. Life isn’t over; there will be a way out for him but he has to grow up and figure things out.

Walter was always excited about an opportunity to push the proverbial envelope with his storytelling. I sent him a childhood favorite, All of a Kind Family. I got back Bad Boy, the memoir about how he dropped out of Stuyvesant High School and hung out in Central Park, reading Balzac in French, following the reading list an English teacher had made for him. She knew that he wasn’t going to stay in school but she told him to keep reading and writing, no matter what. Years later, he remembered her advice about writing. Of course he wasn’t advocating for kids to drop out of school. But Walter wanted high school dropouts to know that it was possible to be successful even if you were coping with challenging circumstances. Walter told me, “I want kids to know that I went through tough times, too. But it worked out. And in my book, I’m going to tell them why. And how I did it.”

When he received a fan letter from 13 year old Ross Workman, Walter wanted to try a new collaboration, co-writing with a teen author. I said to him, “You know, you can fix it yourself.” He told me, I’m only interested if Ross wants to keep working on it.” Two years later, Kick was published. It’s about a soccer player (Ross’s chapters) and his mentor (Walter’s chapters). It was fascinating to read the correspondence between Walter and Ross and watch how Walter taught Ross how to put a book together. Ross wasn’t the only author Walter mentored. Over the years I learned about writers of all ages, some incarcerated, who benefited from Walter’s counsel and expertise. He had so many of his own writing projects that engaged his interest and he was busy ‘round the clock. And yet he still made time to help aspiring writers.

When he received an honorary degree from Amherst College, he heard a lecture about studies in computer modeling. Years later, in 2014, it would appear in the new novel, On a Clear Day, this time featuring an ensemble cast, starring a girl math whiz and set against a futuristic global context. He was trying something different. Even though his hero wasn’t a male urban teen, he didn’t deviate from his message: What do you believe in? And, it’s not too late to make a difference.

Always, Walter was committed to a writing life. He knew that there were things readers needed to know. And they didn’t always have someone who could walk them through it. Walter knew that books could make a difference in their lives, just as they had for him.

My job was to help Walter write the best books he could; to encourage him to push himself as a writer; to help him reach the widest readership. But this is what I learned from Walter. That it was about work and discipline (talent, obviously). That it was possible to be a force for change. To stand by your convictions, and be successful at it, too. His intent was to connect with the young people who didn’t always see themselves in the literature. But the truth is that the truth in his books reached everyone.

Phoebe Yeh is the publisher of Crown Books for Young Readers/Random House. Previously she was an editorial director at Harper Collins Children’s Books; senior editor at Scholastic Press and an editor of the SeeSaw Book Club.

Phoebe Yeh is the publisher of Crown Books for Young Readers/Random House. Previously she was an editorial director at Harper Collins Children’s Books; senior editor at Scholastic Press and an editor of the SeeSaw Book Club. -

Fans Can Vote on the Title & Jacket for the Next ‘Timmy Failure’ Book

“The irreverent illustrated middle-grade series has sold 500,000 copies to date. Rights to the series have been sold in 33 countries, and it has been translated into 30 languages. In …

-

‘It’s Possible’ Series: Resonating with Walter Dean Myers

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Miriam Altshuler

Walter Dean Myers and I began working together over twenty-five years ago.

At the time, diversity in publishing was not discussed nearly as much as it is today. Even back then, Walter understood the need for all children to have their stories told in books that mirrored their diverse lives. Walter’s own story of growing up is well known and comes to life particularly in his memoir, Bad Boy. He and I spoke often about his desire for young readers to have books in which they could see and understand themselves. He knew early on how important this was for every child, and he wrote about the children he understood so well: African Americans who grew up in urban areas, and children who needed to read and learn from books just like he did while growing up in Harlem. He also wrote for all reluctant readers and children who did not have parents or other people in their lives to read to them. He wanted everyone to have books to read (no matter their color or background), but most of all, he wrote for young African American boys.

I remember going to ALA for the first time with Walter after his wonderful novel, Monster, won the inaugural Michael Printz Award. A teacher from Detroit came up to him and told us a story about her classroom. She taught ninth grade English and all her students were African American. She could barely get them to show up for class. After reading Monster herself, she decided to read a chapter to the few students who did come. They were riveted. The next day a few more kids showed up, and she read more of the novel. And the day after that more kids came, until the day all the kids were present in the class and she read Monster from start to finish. Her students were hooked and they began coming to class on a regular basis. She told this story with tears in her eyes (and I can never tell it without tears in mine). She told Walter his book reached these inner city African American children in a way that nothing else had. Monster helped them to see themselves, their lives, and the choices they made.

Walter, of course, had always understood the power of words and stories.

I learned more from that one day than I have in much of my career. Walter knew how to reach children through all kinds of books: contemporary novels, historical novels, poetry, and nonfiction. We spent a lot of time talking about all of his book ideas and how to make them the best they could be. Walter’s ideas were endless, but above all they had to resonate. He knew what made a great story. And I knew when he knew he had a great story because he would keep coming back to it until the right idea took shape. He could love a character or love a subject, but until he saw the arc, heard their voices, and could see how the characters came to life, he knew he was not ready to write it. I was often a sounding board for Walter: He would talk, I would listen, and then I would ask questions about a character or how he saw the shape of the story, and Walter would listen to my questions. But until he had it fully planned out—both in his head and on the story board he would create for each book (as he describes so well in his wonderful writing guide, Just Write!)—he knew it was just an idea. Walter had to feel an emotional connection to each character and story.

Walter always wanted to try new things. One of the great joys of working with him was his incredible ability to listen and learn. He always wanted to hear what others had to say about a subject, an idea, or what he had written, and he was captivated by so many things. “That is so interesting,” he would always say. I can still hear that excitement in his voice.

Ultimately, he was true to his belief in a new book in the same way he was true to his readers—when something stuck with him, when he remained interested in it and he kept going back to it, he knew it was a book he wanted to write. I believe, and I know Walter did too, that when a book touched him, it would touch everyone who read it, especially the children who needed it the most—the reluctant African American readers who so badly wanted and needed to hear their own story told by someone who understood them.

Someone like Walter.

Miriam Altshuler began her own agency in 1994 after starting her career and working for many years at Russell & Volkening Literary Agency. She represents both children’s and adult books in fiction and non-fiction.

Miriam Altshuler began her own agency in 1994 after starting her career and working for many years at Russell & Volkening Literary Agency. She represents both children’s and adult books in fiction and non-fiction. -

Encouraging Kids to Read in 2015

The trend for inspiring literacy is seen both in parents of preteens and teenagers: “35 percent of parents of 6- to 11-year-olds along with 28 percent of parents of 12- to …

-

‘Guess How Much I Love You’ Turns 20!

According to Karen Lotz, president and publisher of Candlewick Press (the book’s US publisher), Guess How Much I Love You was the publishing house’s first breakout hit. Now translated into more than …

-

A Letter of Gratitude to Walter Dean Myers

In a letter addressed to the late Walter Dean Myers, Andrea Davis Pinkney — VP and Executive Editor of Trade at Scholastic — introduces next week’s “It’s Possible” series, where five inspiring publishing professionals will share a little bit of their experience with Walter and how working with him helped push his goal of more diverse literature forward. Check back every day next week for new posts.

Dear Walter:

You always had a story to tell. One of my favorites was about the time you spent as a child with your foster mother reading True Romance magazine. This was the beginning of your beginning. Hearing stories being read aloud made an impression that lasted a lifetime. You called this childhood introduction to reading a gift.

I remember thinking, Walter, you are a gift.

Around that time, you were writing Sunrise Over Fallujah, a novel that centers on the war in Iraq, and is the second novel in what has come to be called your “war trilogy.” It is the stunning companion to your seminal Vietnam War novel, Fallen Angels. With each stage of the editing and revision, you delivered your gift ― you poured keen insight into those pages, and made us think about war’s devastating effects. Your gifts continued to come forth while we worked together on your middle grade Cruisers series, and then on one of your final novels, Invasion, a book set during World War II, which completes your war trilogy.

Yes, yes, Walter, you are a gift who shared your deepest self.

You were a Renaissance man from Harlem. And, like a fascinating rhythm on the A train to 125th Street, you brought us along on your Renaissance ride, as beautiful as the jazz played in the uptown neighborhood you so often celebrated in your books.

As an author who is still learning my craft, I sought your advice on the stories I’d written and how best to render them. Walter, you are a gift who told me that the books we write shape a child’s self-image, and have a lasting impact on the souls and psyches of young readers.

I had the great privilege of accompanying you to the May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture you had delivered at the Children’s Defense Fund Alex Haley Farm in 2009. Your remarks had been introduced by Children’s Defense Fund president and founder, Marian Wright Edelman. You rose to the occasion brilliantly.

When I was invited to deliver my own May Hill Arbuthnot Honor Lecture, I cried out to you with great anxiety and trepidation about its crafting and delivery. How would I ever follow in your awesome footsteps? In your wisdom, you reminded me that we each have our own footsteps, and that positivity can walk us through any experience. Yes, yes, Walter, you are a gift that encourages all of us to step into our own stories, and to use these to move forward while helping others along the way.

I’ll always remember the day you came to Scholastic to spend time with a group of African American boys who were visiting from the University of Illinois at Chicago’s reading clinic. These young men called themselves “brother authors,” and they wanted to be just like Walter Dean Myers.

You treated them as if they were your own brothers, and let them know they were already like you, because they’d found themselves through reading and writing.

The boys were especially intrigued by your Newbery Honor and Coretta Scott King Honor Award-winning Somewhere in the Darkness, and they wanted to know what it’s like to win so many medals. You were quick to point out that even with your glittering list of prizes, you weren’t in it for the fame. You were in it for the love of the game.

That’s why those kids loved you and why we love what your message continues to do. You’ve changed the game forever. Through Somewhere in the Darkness, and every book you wrote, you gave a gift that lets us see past darkness. You generously lit a path for the next writer and reader on the road.

In 2012, you were named The National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. Through your platform, you reminded us that “reading is not optional.” During your tenure, you worked with Every Child a Reader and the Children’s Book Council on the planning and direction of your term.

As a member of the Children’s Book Council’s Diversity Committee, I watched with awe as you fielded endless invitations, reviewing each with your eyes on the prize that mattered most ― literacy. You were also an active participant in the CBC Diversity initiative. Your blog post on Authentic Voices was one of the most visited posts in the history of the CBC Diversity “It’s Complicated” forum. That’s because you brought to it your gift of authenticity.

Yes, yes, Walter, you are a gift who constantly showed us that all children matter, and that hope can be found in an open book. At the same time, you dared to ask, “Where are People of Color in Children’s Books?" in your New York Times Opinion piece. That simple question rocked a very heavy boat, and forced all of us to batten down our hatches so that we could ride together on the high seas thrusting forward among the winds of change.

And now, Walter, as we embark upon the three-year anniversary of your appointment as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, we celebrate you with a series of guest posts by five members of the publishing community who worked alongside you. Each shares a bit of their experience with the gifts you brought to them, and how these helped advance the goal of more diverse books. Over the course of the next week, your literary agent, Miriam Altshuler; two of your esteemed editors, Phoebe Yeh and Regina Griffin; Virginia Anagnos, your long-time publicist and Executive VP at Goodman Media; and Jennifer Brown, Director of the Center for Children’s Literature at the Bank Street College of Education, will share their memories.

One of the last projects that you and I had the pleasure of working on together was Scholastic’s Open a World of Possible campaign. As part of the initiative, you wrote a story entitled “I Am What I Read” that was published in an anthology of real-life stories.

In your piece, you say: “Once I began to read, I began to exist.” Yes, yes, Walter, you are a gift who reminded us that our very existence ― our living and breathing and giving to others ― happens when we experience the joy and power of reading.

Walter Dean Myers, if joy is a teacher, you are the master instructor. You are a gift ― our ode to joy. And now, in this CBC series so aptly entitled “It’s Possible,” the time has come to pay tribute to your enduring legacy.

Please let us return your gifts to you.

With gratitude,

Andrea Davis Pinkney

Andrea Davis Pinkney is the New York Times bestselling and award winning author of many books for children and young adults. She is also Vice President, Executive Editor at Scholastic, where she served as Walter’s editor. Andrea has been named among the “25 Most Influential Black Women in Business” by The Network Journal, and is the mom of two incredible teens who love to read.

Andrea Davis Pinkney is the New York Times bestselling and award winning author of many books for children and young adults. She is also Vice President, Executive Editor at Scholastic, where she served as Walter’s editor. Andrea has been named among the “25 Most Influential Black Women in Business” by The Network Journal, and is the mom of two incredible teens who love to read. -

Scholastic Releases ‘Kids & Family Reading Report™’

Scholastic has released a new national survey, ‘Kids & Family Reading ReportTM: 5th edition,’ focusing on the reading attitudes and behaviors of kids ages 6-17 and their parents. The survey also provides data on early literacy …

-

Books for Asia and Publishers Rally for Typhoon Haiyan Relief

In November 2013, Typhoon Haiyan took more than 4,000 lives and displaced 4 million people, while entire towns were washed away or severely damaged. With funding provided by the Australian government, Books for …