‘It’s Possible’ Series: A Place in History

An “It’s Possible” post contributed to CBC Diversity by Jennifer M. Brown

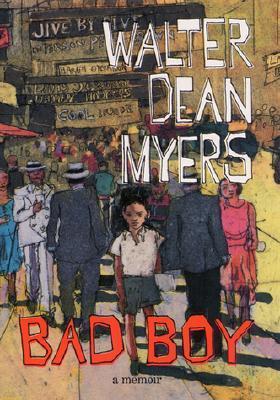

“Each of us is born with a history already in place.” Those words open Walter Dean Myers’s memoir, Bad Boy. The word “history” applies to that of the individual child, born into a family and a set of circumstances. “History” is also tied to a physical place. Walter Dean Myers was profoundly aware of both.

He believed that individuals could change history; he watched them do it, and he was an instrument of change himself. He also had deep ties to his childhood home in Harlem. From his picture book Harlem, illustrated by his son Christopher Myers, to his Newbery Honor book Scorpions and the inaugural Printz winner, Monster, he wrote of Harlem’s glories and its sorrows. If you were lucky enough to hear him tell stories of his youth, he’d describe walking down the street and stopping to talk with Langston Hughes, and attending dances and sermons at “a shouting church,” immortalized in one of the poems in Walter’s collection Here in Harlem.

I was 21 and assistant to Bill Morris, director of library promotion at Harper & Row, when Bill introduced me to Walter. They made a comical pair. Bill, the Southern gentleman at 5’2”, and Walter, a full foot (and then some) taller and a straight-shooter New Yorker. But they were great friends, and had the utmost respect for each other. From this vantage point, I got to hear Walter speak at numerous conferences. Wherever Walter went, he commanded a room, standing head and shoulders above most of the people in it. It wasn’t always what he said that made you tilt forward, trying to eavesdrop. It was the way he listened, followed by the concise response that conveyed how closely he’d listened, sometimes responding to what you hadn’t said.

A year ago, when Walter Dean Myers, as National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, passed the torch to his successor, Kate DiCamillo, he described what he called the most important moment in his two years as Ambassador: “I was in a prison that was loosely run. By that I mean, some talking is allowed among the inmates,” Walter said. When he started to speak, an inmate was talking. “‘Keep quiet, I want to hear this,’ one inmate said to the other,” Walter recalled. “That touched me. I knew this program was working.”

When Walter spoke at the 92nd Street Y, a year into his ambassadorship, he described a conversation he’d had with Langston Hughes when Walter was in his 20s. Hughes had been criticized for writing for “the lowest element of black life,” as Walter put it. Hughes told Walter, “That’s who I want to write for.” In his book Just Write: Here’s How! Walter wrote, “Reading probably saved my life.” For him, reading was not an option, it was essential. He transformed his personal credo into his platform as ambassador: “Reading is not optional.” He also says, in Just Write, “I write books for the troubled boy I once was, and for the boy who lives within me still.” He worried about the kids who begin school behind, and how only 15% of them ever catch up.

He worried about them because he’d been where they were and he’d walked in their shoes. He also wanted to give them hope—if this “bad boy” could turn his life around, so could they. He knew, too, that his stories could appeal to people who had not walked in their shoes. If Walter, as a teenager, could relate to Stephen Daedalus in James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, then books could unite all races and cultures. Books could save the lives of young people everywhere, in myriad ways.

Even after he’d won the inaugural Printz Award, multiple Coretta Scott King Awards and Honors, Newbery Honors, the Virginia Hamilton Award, the Margaret Edwards Award and been named a National Book Award finalist numerous times, Walter continued to challenge himself. Soon after he’d won a MacDowell Colony Fellowship, to spend some uninterrupted time writing in a cabin in New Hampshire, he told me his goal while there was to “slow down.” He wanted to write fewer pages a day. But I don’t think he ever could. He had too much to say.

It’s hard for me to believe that Walter Dean Myers no longer walks the earth. His sense of humor, his world view, his wisdom, remain with me. Hardly a day goes by when I don’t think, What would Walter say about this? What would he notice that I’m missing? How can I pay more attention to what matters? The closing lines of Bad Boy uplift me: “Writing had let me into a world in which I am respected, where the skills I have are respected for themselves…. All in all it has been a great journey and not at all shabby for a bad boy.”

Jennifer M. Brown has been in children’s books for more than 25 years. She writes for School Library Journal, Kirkus Reviews, and is children’s editor of Shelf Awareness. She is also the director of the Center for Children’s Literature at the Bank Street College of Education.