Flooded with Understanding

Contributed to CBC Diversity by author Tamara Ellis Smith

Early in the fall of 2011, Tropical Storm Irene swept through my home state of Vermont, my town, my street and my home—and all of a sudden I was inside Another Kind of Hurricane, my debut middle-grade novel (Schwartz & Wade, 2015) about Hurricane Katrina, in a way I had never imagined.

I began to write Another Kind of Hurricane

in September 2005. The story was born out my then four-year-old son

Luc’s question, “Who is going to get my blue jeans?” as we dropped off a

bag of food and clothing for the Hurricane Katrina Relief Drive at the

Vermont State Police Barracks. I didn’t know how to answer his question.

I didn’t know who would get his blue jeans. But he stayed with me, this

mystery person. And so I began to imagine: What if a Caucasian boy in

Vermont named Henry donated his blue jeans to the relief effort in New

Orleans? And what if an African-American boy named Zavion got them? What

if Henry put his lucky marble into a pocket of those jeans? And what if

Zavion found the marble and wondered who had given him this magical

gift?

Because I was writing outside of my experience, I did my

homework for this story. I read articles and blogs and books—first-hand

accounts of what it was like to be in New Orleans during and after

Katrina. I interviewed people. I watched documentaries. I felt as though

I knew—as best I could—what it had been like during those harrowing

days of the hurricane. I felt emotionally connected to the incredible

people who had survived such a tragic disaster. It was from this place

that I wrote my novel.

Then Tropical Storm Irene hit and Another Kind of Hurricane became exceedingly more personal.

In an odd, reverse sort of process, life imitated art.

I wrote about this in Hunger Mountain.

The visceral and emotional experience of living through Irene (and the

subsequent recovery from that flood) gave me personal experience to draw

on as I revised my novel. But does that mean I was no longer writing outside my experience?

Yes and no.

Am I more suited to tell a story about flood victims because I have experienced a flood? Yes.

Am

I still someone, let’s say, who could borrow money from my family when I

lost so much in that flood? Yes. (And, by the way, I needed to and I

did.)

Did many of the flood victims in New Orleans not have that privilege? Yes.

This

is a small example of a shared experience branching off like the arms

of a river – in this case, the arms center around class. (I wrote more

about this privilege at Emu’s Debuts.) Mitali Perkins articulates this best in her CBC Diversity blog post Is the Race Card Old School?

In the end, she says: “Our job in storytelling is to deploy our adult

faculties of experience, research, imagination, and empathy, and do our

best to follow.”

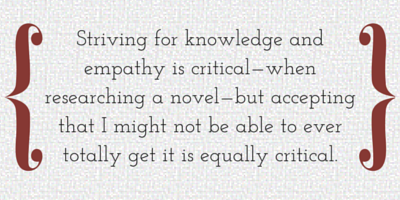

What I have come to realize is similar: Striving

for knowledge and empathy is critical—when researching a novel—but

accepting that I might not be able to ever totally get it is equally

critical. Maybe another way to put it is that weaving a good dose of

humbleness into my quest for knowledge and empathy is vital when I write

about anything outside of my direct experience.

There’s one more thing I have discovered: There is always a space left empty.

The

more I think about it, the more I believe that this space is an

incredibly vital part of the process of writing outside of one’s

experience. Our tendency is to want to fill space. Within the realm of

writing outside of one’s experience, I think we sometimes fill space

with too much knowledge. I know that sounds strange, or impossible, or wrong even. Didn’t I just say that striving for knowledge and empathy means everything? How could it ever not be a good thing to fill ourselves with solid research?

Of

course we need to do research. There is no substitution for that. Nor

is there any justification for not doing that. But I think we have to

leave space too—for that humbleness, for improvement, and even for a

little bit of unease (or even fear) about the fact that we might not get

everything right.

But we especially need to leave space for our readers to insert themselves—to make our stories their stories.

Louise Rosenblatt’s

Reader Response Theory suggests that it is only when the reader enters

the scene and makes meaning from the words running across the page that

the book is fully realized. In essence, a book is not a finished piece

of literature until it is read. I love this. And I believe it.

Rosenblatt

suggests that the text and the reader engage in a sort of circling

spiral dance, as opposed to the notion that the text contains all of the

meaning within it and the reader’s job is to extract that meaning. So

this means that the readers reads a section, gleans some meaning,

applies that meaning to the next section, gleans more meaning, feels

something new, re-applies meaning to the previous section, applies this

new meaning to the next section…and on and on like that.

We talk

about offering kids mirrors and windows so that they can see themselves

and others in our books. The idea of the book not being fully finished

until the reader engages with it creates the opportunity for kids to experience themselves and others. It is a breathtaking and immediate unfolding of feeling and thought and discovery, much like the unfolding of wings.

Leaving

space not only honors the important truth that we can never completely

know someone else’s experience but also nurtures the capacity for kids

to fly.

Tamara

Ellis Smith earned her MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults

from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. She lives in Richmond, Vermont,

with her family. Another Kind of Hurricane (Schwartz & Wade/Random House, 2015) is her first novel and a portion of the profits from the sale go directly to lowernine.org, an organization dedicated to the long-term recovery of the Lower Ninth Ward. Visit her on the Web at her website, on Twitter, and Facebook.