Industry News

-

Darkness Should Be Visible: Robin Wasserman on How “Stephen King Saved [Her] Life”

Wasserman makes the point, contested and defended a few times in recent years, that darkness in children’s books is not only valuable, but necessary. She argues that Stephen King’s adult books …

-

Librarians: Apply for an ALSC Día Family Book Club Mini-Grant!

Via ALSC: “Apply for a Día Family Book Club mini-grant! Intended as an expansion of El día de los niños/El día de los libros (Día), the Día Family Book Club …

-

New Study Finds that Language Gap Between Rich and Poor Children Begins Earlier Than Previously Thought

“The new findings, although based on a small sample, reinforced the earlier research showing that because professional parents speak so much more to their children, the children hear 30 million …

-

Tom Angleberger to Create Book 5 in the ‘Origami Yoda’ Series

“The ‘Star Wars’-inspired series stars Dwight, McQuarrie Middle School’s weirdest student, and his Jedi-wise finger puppet of Star Wars Grand Master Yoda. Antics continue in the series with the introduction …

-

CBC Forum: New Markets, New Opportunities

“Moderator Carol Fitzgerald of the Book Report Network asked audience members to ‘dismiss your preconceived notions about marketing and selling books,’ before asking the panelists to comment on effective methods …

-

Laini Taylor to Release a ‘Daughter of Smoke & Bone’ Novella

The story follows two characters, Zuzana and Mik, as they embark on their first date. The final installment of the Daughter of Smoke & Bone trilogy, ‘Dreams of Gods & …

-

Neil Gaiman on the Future of Reading and Libraries

The Reading Agency lecture was founded “as a platform for leading writers and thinkers to share original, challenging ideas about reading and libraries as we explore how to create a …

-

CBC Diversity: Industry Q&A with Author-Illustrator Don Tate

When you were a child or young adult, what book first opened your eyes to the diversity of the world?

I didn’t read books as much as I should have. I struggled with comprehension and retention. There was plenty of Dr. Seuss and Mother Goose around the house, but I preferred our Funk & Wagnalls Young Students Encyclopedias. That’s where I discovered a multicultural world.

As a child, I thought the world was white. That’s what my world looked like growing up in Des Moines, Iowa in the 1960s and 70s. White people, white books, white movies, white television, white music. Encyclopedias allowed me to see the world from another vantage point. They revealed a world made up of color — brown people of every shade. Maybe that’s why encyclopedias appealed to me so much.

What is your favorite diverse book that you read recently?

I’m a little confused about the term ‘diverse book.’ It’s one of those uncomfortable, elephant-in-the-room terms, that used to mean one thing, but has morphed into something entirely different. It’s an industry code word whose definition still evolves.

I’ve illustrated children’s books for nearly 30 years — trade and educational. When I entered the business back in the 80s, people used the word ‘diversity’ interchangeably with Black or African-American. When someone said ‘diversity,’ I knew they were talking about me. I was often hired to illustrate a text because an editor had a ‘diverse,’ ‘multicultural,’ ‘African-American’ manuscript. However when I hear the term used today, it’s more inclusive, as should be. When someone says ‘diverse,’ they could mean African-American, Hispanic, Asian, Native, LGBT, girls/women, mixed-race, physically challenged, Buddhist — or even white. A better question might be: What is a favorite book that exemplifies diversity? But even that would be a difficult question because I don’t think diversity can be about one or two books. It’s about a body of books: Heart & Soul; Diego Riveria; Dreaming Up!; Around our Way on Neighbor’s Day; Alvin Ho; Jingle Dancer. There’s so many.

If you could participate in a story time with any children’s book author or illustrator (alive or dead) who would it be?

Ezra Jack Keats. It’s funny, but until just a few years ago, I thought Ezra Jack Keats was a Black man —- ha-ha-ha! — but, honestly, I did. He had a way of portraying African-American people authentically. And he did it with soul! In order for a white artist to illustrate Black people, they need to understand our skin color, hair texture, anatomy, or the art will pop off the page as unauthentic. Or at least it will to other Black people. Ezra portrayed Black characters with dignity and pride (though some early critics said otherwise). Interestingly, he did it at a time in history when Black people weren’t portrayed much in children’s literature at all. Ezra’s stories did not focus on the character’s race, racial strife, slavery, civil rights. He told stories with universal themes that every child could relate to. The color of his character’s skin faded as one got into the story. I don’t know that anyone has been able to do that since then.

How do you introduce books featuring characters of color to parents and kids?

I introduce my books to kids by visiting schools and participating in book festivals. I don’t make an issue of race. I tell stories. I draw pictures. I talk about my books. My brown-face characters speak for themselves. Children, regardless of race, are open to my books. Parents, however, can hesitate sometimes. For example, one time at a book event, a white child strolled up and picked up one of my books. He was with his parents, who looked a bit uncomfortable with the situation. He turned to his mother and said, “I want this one,” pointing to my Willie Mays book. His mother smiled in attempt to hide a struggle going on inside her head. But soon her feelings were plastered all over her face: She did not want to buy my book for her kid. After a few seconds of hem-hawing, she responded, “What about one of those books?” She pointed to another author who was signing nearby. Then she pointed to another. Those authors were white. I don’t remember the authors or their books, but they didn’t feature Black characters. To my amusement, the kid did not give up. “I want this book,” he said. I fought off a smile. This has happened more than a few times. I think the more kids— and parents of all races — are exposed to racial diversity in books, the less race becomes an issue.

Authenticity is, of course, key in multicultural literature, and often times reviewers tend to highlight perceived inaccuracies. How do you think this affects the publishing industry’s decision-making process in including or excluding characters and books with diverse and/or multicultural themes?

It’s been my experience as a picture book illustrator, that when an editor has a book with African-American subject matter, written by a white author, they’ll bring on a black artist, if possible. They do this, I’ve been told many times, figuring a Black artist will bring a greater sense of authenticity to the story. I agree and disagree. As a Black artist, I know my people, culture, life experience. I can make it real. But so can an artist of another race, if they do their research like they should — Ezra Jack Keats, again, a good example.

The practice of matching a Black author to a manuscript with Black subject matter creates a niche for Black artists. Filling that niche keeps manuscripts coming our way, as long as the artwork is quality and deadlines are met. On the flip side, it can also put us into a box. I love illustrating books about my people. I am thankful to the editors and art directors who provide me work. But where are the offers to illustrate a manuscript with a white protagonist? Will that come along? Or what about a manuscript featuring a cute dog, funny pig, or crazed-out carrot? I can do a crazed-out carrot.

How can we reconcile the prevalence in reviews of readers wanting to like or sympathize with the protagonist, and our call to write people with whom they fundamentally differ?

I don’t know if the publishing industry can reconcile with readers (white readers?) who are less interested in books with protagonists who differ from them. It’s a free country, you can’t force ‘em to read what they don’t want to read. But I think if you can reach their children, you can affect the future.

When children are raised with books featuring multicultural characters, protagonist who are different from them are no big deal. As a Black male, I didn’t very often have the choice between a protagonist who looked or didn’t look like me. If I was going to read a book, it would likely feature a white protagonist. Period, like it or not. So today I can read a book like The Marbury Lens and not get tripped up on the race of the character.

As someone who reads, loves, and often reviews children’s literature, please provide what you feel are the three most important things to keep in mind when writing a diverse character or about a different culture.

Be wary of stereotypes. Check your work by checking with others. I belong to several writing critique groups. I’m the only person of color within those groups. When my friends write about other races, I’m careful to point out stereotypes or things that might be offensive to people of color. My friends aren’t racists in the least bit, but they’re human. They have preferences and biases, same as I do. But they’ve probably never been the victim of racism, and so they just don’t know when the line has been crossed.

The question of stereotyping can be fine line to walk, in my opinion. Lets say a white author writes a story about a Black teen, who lives in an urban neighborhood and likes to play basketball, is raised by a single mother, whose father is dead or in prison. Is this stereotypical? Yes, kinda. But is it realistic? Oh, yes! Should a white author avoid this kind of imagery for fear of being called out on stereotyping? No, I don’t think so. But I advise that they check themselves by checking with Black people. And if they don’t know any Black people, well, there’s where the problem will begin.

If more books were published like Varian Johnson’s My Life As A Rhombus, books featuring suburban, Black math-whiz teenagers, in homes with two caring and hardworking parents, the other stuff wouldn’t likely be an issue anyway. Balance is what’s needed.

Don Tate has illustrated many books for children, including She Loved Baseball, Ron’s Big Mission, Duke Ellington’s Nutcracker Suite. He is also the debut author of the award-winning It Jes’ Happened: When Bill Traylor Started To Draw. Don lives in Austin, Texas.

-

2013 National Book Award Finalists Revealed

2013 Young People’s Literature Finalists Kathi Appelt, The True Blue Scouts of Sugar Man Swamp Atheneum Books for Young Readers/Simon & Schuster Cynthia Kadohata, The Thing About Luck Atheneum Books for Young …

-

FableVision Studios and Reading Is Fundamental Present Free Reading Apps for Kids at Boston Book Festival

BOSTON – FableVision, a Boston-based group of education media development and publishing companies, and Reading Is Fundamental (RIF), the nation’s largest children’s literacy nonprofit, have teamed up to develop and distribute …

-

Currituck County School Board Votes to Keep Challenged Library Book on Shelves

The Kids’ Right to Read Project (KRRP) is celebrating a 4-1 vote by the Currituck County School Board that will keep Tanya Lee Stone’s A Bad Boy Can Be Good for …

-

How is the World of Children’s Picture Books Changing?

The Changing World of Children’s Picture Books from Penguin Random House

-

Send in Your Presentation Proposals for the 2014 YALSA Symposium

YALSA’s 2014 Young Adult Literature Symposium will gather together librarians, educators, researchers, authors and publishers to explore what’s ‘real’ in the world of teen literature. Join YALSA as we discuss …

-

What Books Would You Pick For a List of Great Children’s Books?

“Great stories never grow old! Chosen by children’s librarians at The New York Public Library, these 100 inspiring tales have thrilled generations of children and their parents — and are …

-

Powering Global Education: First Book to Provide Books and Digital Content to 10 Million Children Worldwide by 2016

NEW YORK – In July, 16-year-old Malala Yousafzai mesmerized the United Nations – and inspired millions watching – by urging a united effort against illiteracy, poverty and terrorism and calling for free, …

-

This Week on Girls Scouts’ The Studio: The Classroom Series Author Robin Mellom

“A writer notices things in the world—a thought, an idea, or something in the environment—and puts it into words. That moment, that treasure, is now something to be shared. Do …

-

New Grant to Encourage Diversity in Science Fiction Writing

The grant would be administered by the Speculative Literature Foundation, a non-profit organization that promotes science fiction and fantasy and encourages new writers of both adult and children’s genre literature. …

-

Ask a Librarian: Find the Perfect Book for Your Child

“From girls who save the world to American history guaranteed to gross you out, our picks will help any child love reading even more”, says Noodle. Brought to you by: …

-

Kids’ Right to Read Fights Challenge to ‘Invisible Man’ During Banned Books Week

KRRP, founded by the National Coalition Against Censorship and the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression, defends the freedom to read in schools and libraries nationwide. KRRP is sponsored in …

-

CBC Diversity 101: Blurring the Lines Between Familiar and Foreign

Part II—A Focus on Dialogue

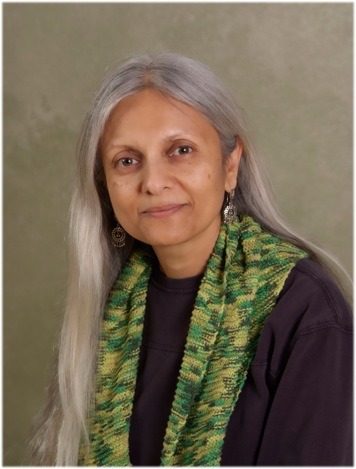

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Uma Krishnaswami

My Personal Connection

The books you read as a child are as real as the places you live in or the people around you. They whisper to you of the possibilities the world can offer, like mental pathways into your own as-yet-unlived future.

In that category, Rumer Godden gave me permission to write. Kipling both enchanted and troubled me; only many years later did I understand my own need to write about the country he depicted with his strange colonial mixture of tenderness and disdain. But as a child of the late 1950s growing up in India, I cut my reading teeth on Enid Blyton.

I learned a lot from Enid about humor, family, friendships, and the pleasure of racing along a swiftly unfolding plot. Now, thinking back, I am pretty sure that I also learned how not to write dialogue.

Stereotypes/Clichés/Tropes/Errors

Consider this passage. The characters, including Kiki the parrot, have arrived in a fictional place called Barira. They’re met by the hotel manager:

‘Ha – what you call him – parrot!’ said the little manager. ‘Pretty Poll, eh?’

‘Wipe your feet,’ said Kiki, much to the man’s surprise. ‘Shut the door!’

The small man was not sure whether to obey or not. ‘Funny bird!’ he said. ‘He is so much clever! He spiks good! Polly, polly!’

‘Polly, put the kettle on,’ said Kiki, and gave a screech that made the man hurry out of the room at once.*

*(US readers, note that the punctuation is correctly quoted from this UK edition)

Note the reference to the speaker as “the little manager.” In the allocation of power, even the talking parrot is higher up than this adult character in a developing country. Note the deliberate errors in his speech, his hesitation in choice of words, his mildly mangled pronunciation and syntax. All of it results in making the foreigner seem an object of ridicule.

From The Valley of Adventure, here’s a passage where the children talk about the natives of the country they’ve landed in:

‘What country are we in?’ said Lucy-Ann. ‘Shall we be able to speak their language?’

‘I don’t suppose so for a minute,’ said Philip. ‘But we’ll just have to try and make ourselves understood.’

One wonders if they pulled it off by shouting or speaking… very… slowly.

This isn’t meant to indict Enid Blyton as a person or as a writer. In Blyton’s 1940s world, speakers of English were “us” and everyone else was “them.” Social psychologists call this “ingroup bias.” We all have some version of it. As writers we need to become aware of our own biases as we create the voices of our characters.

Things I’d Like to See

Here’s what I tell my students in the MFA program in Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts.

1) In dialogue, create speech patterns that don’t stereotype. This means listening, really listening, for character voice, a process that is equal parts meditative practice and craft. If you don’t listen closely enough, you end up transcribing real conversation, and we all know the paradox in that—real speech, written down as dialogue, sounds fake. Take that across cultural lines, and those transcriptions sound not only fake but patronizing.

2) Use colloquial speech—please don’t take all the contractions out. Personally, I’m tired of hearing South Asian characters who sound like Gunga Din. When you’re writing contemporary fiction, let your characters sound as if they live in the same century as we do. You’re after cadence, not caricature.

3) When characters use a sprinkling of languages other than English, allow the meaning to emerge through context. Parenthetical translation isn’t incorrect, exactly, but it can become annoying if it’s overused. Sometimes mood matters more than literal definition.

4) It really helps if you have at least a working familiarity with the language you’re trying to sprinkle in. Otherwise your characters are going to sound as if they’re reciting from tourist phrase-books.

5) Get into your characters’ hearts and souls, not just their thoughts. Emotional resonance is what you’re after, regardless of what kind of story you’re writing. Dialogue that is too cerebral will feel flat, as if your characters were talking heads. Then again, make sure that the character’s emotions feel true to his or her cultural context. Oh, and while you’re at it, make sure you’re not stereotyping that context either.6) Whether you’re writing within or out of your own cultural context, let dialogue do the work it’s meant to do—show subtext, hint at unspoken emotions and interpersonal dynamics, affect the momentum of the story by driving it forward or lingering for a glimpse into something deep.

Suggested Reading

- In This Thing Called the Future by J.L. Powers, Zulu words are used in dialogue with subtlety and sureness. The author is aware of the choices she makes in matters like standardizing plural forms for clarity or employing nouns in sentences.

- Tell Us We’re Home by Marina Budhos. In this novel with a braided structure, the voices of three immigrant girls are perfectly tuned.

- Where the Mountain Meets the Moon and Starry River of the Sky, by Grace Lin. The dialogue in both books seems an effortless extension of the storyteller’s voice.

- The Revolution of Evelyn Serrano by Sonia Manzano integrates Spanish words and phrases into dialogue with ease and fluidity. Each spoken voice is clear and distinct.

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of The Grand Plan to Fix Everything and The Problem With Being Slightly Heroic, both from Atheneum Books for Young Readers.