Uncategorized

-

How I Got into Publishing: Shifa Kapadwala

Contributed by Shifa Kapadwala, Publicity Assistant at Simon & Schuster Children’s Books

I’m from a South Asian immigrant family. For my traditional parents, a woman’s ultimate end goal should be getting married and taking care of a family. It’s no surprise that I don’t share this exclusive view, and I credit reading with helping me understand a culture I didn’t experience at home. I learned about things like the kinds of foods that were eaten for dinner or lunch; the different types of relationships between children and their parents; and social interactions and phrases more commonly used in mainstream Western culture. Though it was extremely hard to find Indian characters to relate to in the books I read throughout my academic career, it was literature that would help me understand the world around me.

It became more evident to me that I wanted to work with books—but the question was how. When I finally connected the fact that the little logos on the spine of my books stood for publishing houses and that there were actual people who worked to bring books out into the world, I decided I wanted to pursue publishing. Deciding was one thing, but pursuing was an arduous path.

When I shared my plans with my parents, there was… tension. Their notion of a family-oriented daughter and my career-oriented self caused many issues. When my dad found out I wanted a career, he only supported my being a lawyer and offered to pay for law school, but nothing else. I knew, ultimately, I would have to support myself financially. Though publishing doesn’t match a lawyer’s salary, I chose to strive for happiness and self-satisfaction.

My determination pulled me through college. The year after, I worked long hours as a writing tutor to earn the money I needed to put myself through the Columbia Publishing Course, a place that finally allowed me to immerse myself in the world I wanted. I hopped between internships, networked with people in the industry, researched imprints, buzzed books, kept up with the latest industry news , and applied to countless jobs, all while maintaining a part-time job to support myself.

I kept trying and eventually ended up as a publicity assistant at Simon & Schuster Children’s Books, where every day is a new adventure. Though my parents still wish I had gone the traditional route, they finally understand and respect—and maybe even appreciate, to some degree—the resilience and hard work it took for me to achieve my dreams. After all, they helped to instill these values in me. Although I don’t expect them to fully understand my career goals or the struggles of living in two different cultures with separate expectations, I’m certainly a lot happier working my way up in an industry I love.

Shifa Kapadwala is currently a Publicity Assistant at Simon & Schuster Children’s Books. Born and raised in New York, she graduated from CUNY Queens College and later, the Columbia Publishing Course. When she’s not immersed in the lives of fictional characters, you can usually find her hunting for her next favorite coffee shop, or at bakeries devouring all the sweets. She tweets at @ShifaKaps111.

-

“I Just Don’t Identify with the Character”

Contributed by Kate Sullivan, Senior Editor at Delacorte Press

These days, many working in the industry have heard the news and are on board with the mission: it’s time to diversify the book market. Publishing is an ecosystem, and every level needs to be committed to making changes if this mission is to succeed.

As an editor, I think a lot about my piece in this effort, and I’m avidly watching what other editors are doing to make it happen. Recently, some conversations I had on Twitter surrounding #ownvoices and #divpit made me reflect about blind spots that even the best intentioned ally or advocate editors have—including myself—and I want to share those revelations so that we can keep pushing the efforts forward.

I know many editors who are ready for change, and are embracing it. They’re calling to the heavens, to Twitter, lunching agents, asking and begging for more diverse submissions. And… honestly, we haven’t been super successful yet. At least, I know I’m not the only one discouraged by the limited progress. Some authors of color or marginalized voices are getting bigger and better book deals but not enough. I’m seeing more books that feature characters of different ethnicities or backgrounds and sexualities, and fantasies inspired by different cultures, but most of them aren’t written by diverse authors. It’s progress of a sort, but we need to push further and do better.

So if editors are advertising that we’re open and ready, why isn’t it working yet? First of all, if we’re acting within the system that is the problem, we’ll never fix it. We can’t use our usual methods of expanding our lists to cover more diverse subjects and authors because it’s the very method that has been failing those authors for so many years. It’s like emailing IT to tell them that your email is broken.

In regards to diverse authors, the common refrain I hear from frustrated editors is: “the manuscripts just aren’t being submitted to me.” Well, no. If marginalized people grew up without seeing themselves in books, why would they try to join traditional publishing? We must go to them, was the point that Sarah Hannah Gomez made on Twitter last month, when she challenged agents to find marginalized voices on social media and invite them to submit. Why can’t editors get out of their comfort zone, too, and find short fiction written by marginalized voices and encourage those authors; email MFA professors and ask to reach out to students; and get referrals from the few diverse authors we already have on our lists?

How are you even on Twitter & NOT seeing diverse voices? This is 1 of the few places we thrive. Like how bad are you at internet #subtweet

— sarah HANNAH gómez (@shgmclicious) February 6, 2016Another refrain I hear a lot from other white editors when talking about the struggle to get more diverse books: “if they were as good as the other stuff in my pile, of course I’d acquire them.” But is that fair? Are they as good, but you can’t see it because of a blind spot? Analyzing manuscripts for acquisition is sometimes an emotional or gut-based reaction, and now and then editors don’t have the time to plumb deeper than that. A common pass letter to an author might say “I didn’t connect to the voice,” or “I didn’t identify with the character.” If you’re a white editor reading this, pause for a second and think about how an African American or Native American might feel getting that pass letter. I imagine they probably think to themselves: “Of course you don’t connect to the character. You’re white. You’ve never been discriminated against like this.”

Another thing we can do to break the system that keeps out diverse authors is simply to check ourselves. I believe that “I didn’t connect to the character/voice” is unacceptable when it comes to diverse perspectives. If most editors are white and straight and middle or upper class, of course they won’t “identify” or “connect” with a diverse perspective. For those manuscripts, many of us should take a pledge to examine it in more detail before moving on.

- What is it about the character that you didn’t

connect with? If it’s at all race- or sexuality-based, might it be worth

reading on? If not, consider sharing your

specific analysis of what wasn’t working

with the author or agent.

- If you don’t believe the story and you’re passing

because the race is “too prominent”, take another look, and try to “suspend (white)

disbelief”.

- If your problem was in not connecting with the

voice, analyze it at the sentence level: Are you not connecting with the

writing, or is it that you’re not connecting with the race or sexuality of the

character? If the writing is weak, say why in your pass letter. If it’s good, keep

reading or share with a colleague for a second read, even if it’s not for you.

- Is it a problem with pacing, story structure, or use of perspective that is leading you to pass? All are reasons not to connect with character or story that have nothing to do with identification.

The fact is: marginalized voices have the deck stacked against them because white straight middle or upper class editors can’t identify with their perspective. The level of analysis required from the above questions really only takes an extra 15 minutes of commitment from editors, but that level of feedback can make all the difference for an author. So even if you’re passing, you might be giving them a leg up that they might not otherwise get. If you’re really committed to your alliance, I know of an editor who reads the entire manuscript any time she gets a submission from a diverse author, so that she can give it the best chance, or provide richer editorial comments.

In her article “Your Manuscript is Not a Good Fit”, Paula Lee Young points out that publishing is a cultural system pervaded by whiteness and, I would add, pervaded by a certain level of economic security. And in that system, many gatekeepers are going to have blind spots borne out of experience and privilege.

A glass ceiling would be an improvement on this feeling of running everywhere into invisible electrical fences shrugged off as paranoid delusions by those who aren’t shocked every time they attempt pass through them.

In other words, we’re all standing on the other side of that fence saying “I want more diverse books, I want to change the system” and not working outside of that very system. Gatekeepers and allies and advocates can actively open the door we didn’t even realize we’d left half-closed—we just need to think creatively to see around our blind spots. These two ideas—reaching out and thinking longer—are just the tip of the iceberg.

Kate Sullivan grew up in Belgium, the daughter of an air force colonel, where the tiny american library skipped straight from middle grade to adult fantasy and science fiction, which is where she fell in love with reading. She has worked on several NYT bestsellers, edited four Lambda finalists, and one book she edited has been turned into a film, and is currently a senior editor at Delacorte Press working on YA and middle grade.

- What is it about the character that you didn’t

connect with? If it’s at all race- or sexuality-based, might it be worth

reading on? If not, consider sharing your

specific analysis of what wasn’t working

with the author or agent.

-

National Ambassador Gene Luen Yang’s Reading Without Walls Podcast: Episode 1 with Kate DiCamillo

Through his platform, “Reading Without Walls,” Yang hopes to inspire readers of all ages to pick up a book outside their comfort zone. See Yang’s inaugural interview with his predecessor …

-

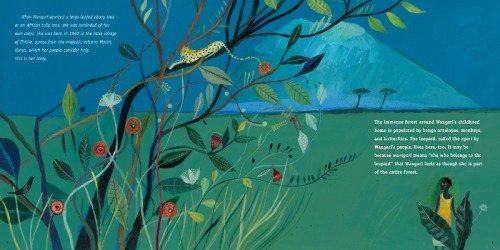

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Wangari Maathai’ illustrated by Aurélia Fronty

Wangari Maathai: The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees by Franck Prévot, illustrated by Aurélia Fronty (Charlesbridge, January 2015). All rights reserved.

-

97th Annual Children’s Book Week Bookmark Revealed!

Download your free bookmark and activity sheet at bookweekonline.com! This year’s bookmark is designed by 2015 Children’s Choice Debut Author-finalist Cece Bell, creator of the graphic memoir El Deafo! It’s the perfect companion for all your …

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘The Crow’s Tale’ by Naomi Howarth

The Crow’s Tale by Naomi Howarth (Frances Lincoln Children’s Books/Quarto Children’s Group, October 2015). All rights reserved.

-

Gear Up at the Book Week Store!

Gear up for the 97th annual Children’s Book Week (May 2-8) while supporting Every Child a Reader, a non-profit dedicated to instilling a life-long love of reading in children. Shop …

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Red’ by Jan De Kinder

Red by Jan De Kinder (Eerdmans, March 2015). All rights reserved.

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Peace is an Offering’ illustrated by Stephanie Graegin

Peace is an Offering by Annette Lebox, illustrated by Stephanie Graegin (Dial Books/Penguin Young Readers Group, March 2015). All rights reserved. @penguinrandomhouse

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘One Family’ by George Shannon, illustrated by Blanca Gomez

One Family by George Shannon, illustrated by Blanca Gomez (Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Macmillan Children’s, May 2015). All rights reserved. @macmillankids

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Mango, Abuela, and Me’ illustrated by Angela Dominguez

Mango, Abuela, and Me by Meg Medina, illustrated by Angela Dominguez (Candlewick, August 2015). All rights reserved.

-

Gene Luen Yang Lends Support to Highlight the Transformation of Libraries as 2016 National Library Week Honorary Chair

CHICAGO — Libraries of all types consistently transform lives through free access to technology, digital literacy, career development, and opportunities for community engagement and lifelong learning. In celebration of the invaluable …

-

Diversity in the News: February 2016

The newsletter is a valuable resource for librarians, teachers, booksellers, parents and caregivers, publishing professionals, and children’s literature lovers. Find thought-provoking articles, diverse new releases, and more in this month’s issue and sign …

-

Into the Trenches

By Julie Bliven,Editor, Charlesbridge

As an editor, I wish I had more opportunities to see first-hand how young readers interact with the books I’ve worked on. I gauge reader responses from sales figures, reviews, and blog posts. I also solicit blunt commentary from my niece and nephew. But that’s about all I’ve got.

In the aftermath of the controversy surrounding A Fine Dessert and A Birthday Cake for George Washington, I wondered a lot about how kids might respond to these particular books. And I wondered how the adult reader would discuss these books with kids. What would I say? This got me thinking about the books I’ve edited: How might I discuss issues like race, class, gender, sexuality, and disability in these books? And why do these conversations matter?

I felt compelled to head into the trenches. Armed with apprehension, I joined the kindergarten classroom of a friend and teacher in the greater Boston area. These were my goals:

- Read one multicultural picture book that I’ve

edited.

- Read one multicultural picture book recommended

by the teacher.

- Discuss the books, encouraging diverse viewpoints. (This particular class of twenty-one has six

students whose first language is not English, and four students of color.)

- Check my own biases by asking and answering questions literally and objectively. (For instance, avoid discussing elements in the text—like a soup kitchen or Arabic—using words like “good,” “different,” or “other.”)

Here’s what happened when we read the books:

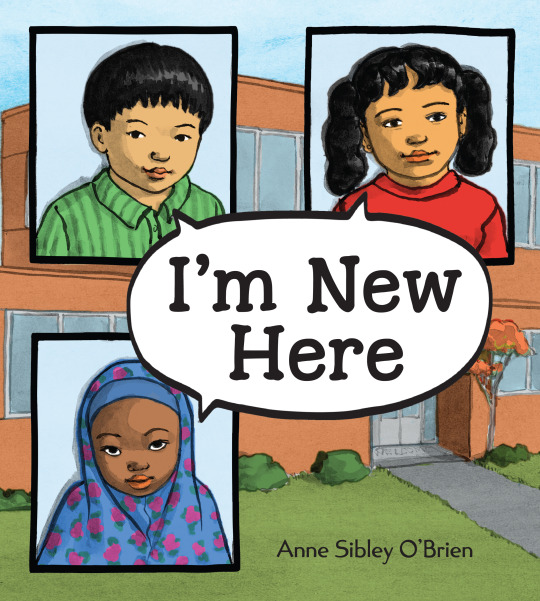

I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien

This was the book I edited. It’s the story of three immigrant children from Guatemala, Korea, and Somalia. They are new to the United States and initially struggle to read and speak English, make friends, and fit in.

First I asked the kids what they thought the book would be about. One girl called out, “They’re from Ireland!” She explained that people who come to America can be from there.

Later I asked questions like “Have you ever been new? What does it feel like?” Responses ranged from “Weird!” to “Awesome—you meet new people!” to “Bad, because you don’t know what to say.”

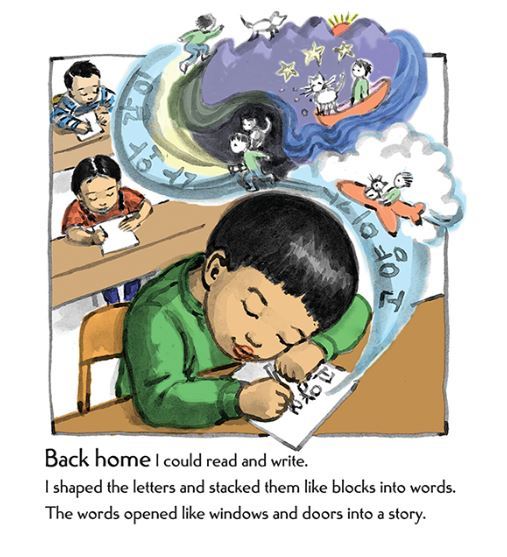

When we came to this page, a boy yelled out, “I can’t believe he’s sleeping in school!” I didn’t know if this was about the shape of the Asian character’s eyes. I wasn’t sure I knew the “right” way to respond. So I asked more questions. The student interpreted the thought cloud as a dream sequence. Mystery solved! I also talked about the illustrator’s choice of perspective: If we stood over someone who was looking down at his paper, it might appear to us—from above—that his eyelids were closed. And suddenly they were telling me ways they like to draw things.

When I discarded my own assumptions and asked more questions, the story and conversation led to illuminating places for all. And isn’t this why these conversations matter?

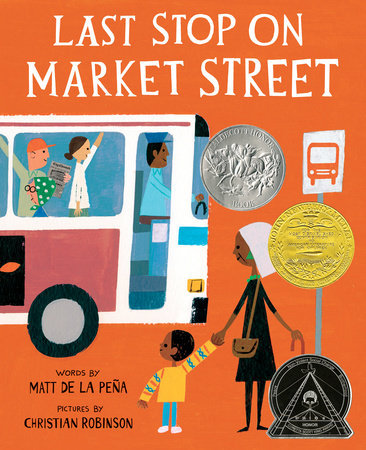

Last Stop on Market Street by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christian Robinson

This was the teacher’s recommendation. It’s the story of CJ and his nana’s bus ride after church. They eventually end up at a local soup kitchen, serving others.

I had to explain that a soup kitchen is a place where food is offered to the hungry, for free. “For FREE!?” an astonished voice asked. Another kid pointed at an illustration and declared, “But that man’s not poor. He has sunglasses. Why is he there?”

I asked if we can look at others and tell whether or not they are poor.

One girl had an answer: “Not if we were all naked.” I was floored by her reflection on physical markers of class. The word “naked,” however, sent the kids into fits of giggles. The girl blushed. But her words opened up a deeper discussion.

I was amazed by how many interpretations of both books were at play. In my editing bubble, how can I imagine all these nuances—not to mention address them? I can’t. But I can keep talking to kids and reading them books. I can keep talking to adults about books, too. In both scenarios, if I remember to ask open questions and listen carefully, I imagine I’ll be better able to gauge what contributes to a book’s capacity for inspiring honest and sometimes complicated conversations.

Julie Bliven is an editor at Charlesbridge. She holds an M.A. in Children’s Literature from Simmons College. If you’re a parent, teacher, or librarian looking for new ways to approach storytime, Julie recommends Reading Picture Books With Children: How to Shake Up Storytime and Get Kids Talking about What They See, by Megan Dowd Lambert.

- Read one multicultural picture book that I’ve

edited.

-

Ninth Annual Children’s Choice Book Awards Finalists Announced

KIDS & TEENS TO DETERMINE THE WINNERS BY VOTING AT CCBOOKAWARDS.COM FROM MARCH 8- APRIL 25, 2016 New York, NY — February 16, 2016 – Every Child a Reader (ECAR) and the Children’s Book …

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Voice of Freedom’ illustrated by Ekua Holmes

Voice of Freedom: Fannie Lou Hammer: The Spirit of the Civil Rights Movement by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Ekua Holmes (Candlewick, August 2015). All rights reserved.

-

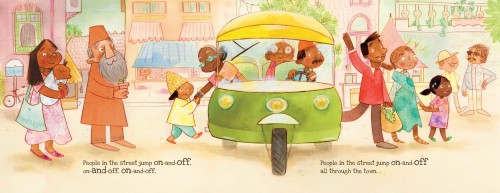

#DrawingDiversity: ‘The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk’ illustrated by Jess Golden

The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk by Kabir Sehgal and Surishtha Sehgal, illustrated by Jess Golden (Beach Lane Books/Simon & Schuster, January 2016). All rights reserved. @simonkidsuk

-

Give a Child a Book of Hope

By Darcy Pattison, Author

I appreciate that the CBC Diversity Bookshelf addresses all sorts of diversity, from ethnic to family situations and beyond. If you glance down their list of 67 topics on the Goodreads Bookshelf, there’s likely a topic that tugs at your heart.

In sixth grade my parents divorced and my mother remarried, this time to a man who was an alcoholic. Several years later, she divorced him and soon remarried — again to an alcoholic.

Despite being an avid reader, I certainly never saw my situation reflected in children’s books! Yet 11 million children live with alcoholic parents (http://www.alcoholism-statistics.com/family-statistics/). Add in those who live with parents who abuse other substances, and it’s a huge demographic that faces overwhelming situations. Often it leads to messy divorces, single-parent families, and other special needs.

Why aren’t these situations represented more in children’s books? Partly because difficult family situations aren’t entertainment.

So, do we write children’s books to entertain, to teach, or to stand on a soapbox? The answers are complex. I wrote my contemporary retelling of the Hansel and Gretel story, Saucy and Bubba, because I wanted my experiences to help children facing caregivers who are substance abusers. I wanted those kids to know it’s okay to want to be safe. It’s okay to need help and to ask an adult for help. It’s okay to want your Daddy to love you and to expect that he will take care of you.

Near the story’s climax, Saucy is hiding under a truck and her father is searching for her. At one point, he leans against the truck, not knowing that Saucy is close enough to touch him. She yearns for Daddy to find her, but she holds back because of the alcoholic stepmother, Krissy. When Daddy goes back inside the house with Krissy, Saucy makes the difficult decision to live with her aunt until things are better.

Scenes like this one bring a certain darkness to a story, even if the events carry the weight of truth. It’s in the tradition of Dicey’s Song by Cynthia Voigt, and The Great Gilly Hopkins by Katherine Paterson. Both of these award-winning books tell of painful truths, but they manage to do so with respect for the child reader. I especially like Paterson’s statement that she always ends her stories with a note of hope. Fortunately, Saucy’s story also ends with hope that the family will work things out and come back together.

In the end, I write to tell a truthful story that will touch someone deeply; I write with the reader — the troubled child — in mind. And children need many things from the pages of a book: entertainment, escape, sympathy, or a deep identification with a character. And most especially, children need hope.

Darcy Pattison has three novels on the CBC Diversity Bookshelves. Saucy and Bubba (sample chapter) is a contemporary retelling of the Hansel and Gretel story with characters who live with substance abuse caregivers; Longing for Normal is the story of two foster kids who are fighting for a place to call home—using just a simple bread recipe; Vagabonds is an American animal fantasy that is a metaphor for the immigrant experience. Translated into nine languages, Darcy’s book, The Journey of Oliver K. Woodman was an Irma Black Honor Award winner and her other books have received starred reviews in Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus, and BCCB.

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton’ by Don Tate

Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton by Don Tate (Peachtree, September 2015). All rights reserved. @peachtreepublishers

-

#DrawingDiversity: ‘A Dog Wearing Shoes’ by Sangmi Ko

A Dog Wearing Shoes by Sangmi Ko (Schwartz & Wade/Random House Children’s Books, September 2015). All rights reserved. @randomhouse