Blog

-

Second Part of J.K. Rowling’s New Writing on Quidditch Now on Pottermore

Today the second part of J.K. Rowling’s entertaining new writing on the magical sport of Quidditch, is released on Pottermore, the digital platform for Harry Potter. The first part of …

-

CBC Diversity: Mark von Bargen — How I Got into Publishing

Senior Director of Trade Sales for Children’s Books at Macmillan

Growing up in South Jersey, my dream was to work in a record store. Remember those? Specifically, the Wee Three Record store in the Moorestown Mall. The closest I ever got was a summer job at Kay-Bee Toys. Going to the mall in those days was THE EVENT. First with your parents, hoping you’d be able to spend time in YOUR stores, and then getting a little older, riding your bike across forbidden busy roads to get to … THE MALL. Wee Three wasn’t a great store if you compare it to bigger brothers like Sound Odyssey and the epic Tower Records in Philly, but it was ours. This was the place my friends and I would go to get the music we loved to hear on FM radio. Among the other stores in that mall was a little shop at the Sears end called, appropriately, The Book End. They had a robust selection of my favorites: Mad Magazine books, Beatles books, and Zander Hollander Baseball Annuals. I never thought about working there. It all seemed too intimidating.

Growing up in South Jersey, my dream was to work in a record store. Remember those? Specifically, the Wee Three Record store in the Moorestown Mall. The closest I ever got was a summer job at Kay-Bee Toys. Going to the mall in those days was THE EVENT. First with your parents, hoping you’d be able to spend time in YOUR stores, and then getting a little older, riding your bike across forbidden busy roads to get to … THE MALL. Wee Three wasn’t a great store if you compare it to bigger brothers like Sound Odyssey and the epic Tower Records in Philly, but it was ours. This was the place my friends and I would go to get the music we loved to hear on FM radio. Among the other stores in that mall was a little shop at the Sears end called, appropriately, The Book End. They had a robust selection of my favorites: Mad Magazine books, Beatles books, and Zander Hollander Baseball Annuals. I never thought about working there. It all seemed too intimidating.

Flash forward to the late 80s. Armed with a History degree from Rutgers, I was living in Philadelphia and needed to get a GRE test book. I went to the Encore Books store in Rittenhouse Square. This was a beautiful split-level store in Center City. They had everything. They had the Barron’s book I needed. They had a sign in the window for their Management Trainee Program. They also had a beautiful girl working behind the counter with a Welsh accent. I was interested in all of the above. The Management Trainee program sounded great, especially if it would help me on the Welsh front. I had lots of questions about the job, most of them revolved around whether this would be in the same store. Answer: “For now, yes, but there is an opportunity to work in lots of stores!” Who wanted that? I got the job, worked there for a month, and was transferred to the store in North Philly on … Welsh Road. Oh, the irony.

My Book End feelings re-surfaced. It was intimidating at first, especially dealing with customers. I was amazed at how the staff knew every book that was in their store. And where it was! After a while, I also became versed in what we had, down to the exact shelf. Something about working 50+ hours a week will do that to you. The other part of working in a store that impressed me was that our store was like a little library. Whatever subject you were interested in, we had something there. I loved that feeling. The store was like our home. We could also order books to build up certain sections, but they had to be sections that were popular. We had a lot of fun building up our Science Fiction, True Crime and Romance section. Fantasy, Sex and Violence was in the air. And it was selling. I worked at Encore for six years, moving up to store manager and then spent 2 years on the road as a merchandiser setting up new stores. Looking back, I have many fond memories of those days, except for the awful maroon aprons they made us wear.

Flash forward to the mid 90s. Unloading trucks in the rain, covering absentee shifts on Friday nights, and wearing maroon aprons can get tiring after a while. Some of my friends had made the big time, and worked at … Baker & Taylor. Cue the angel music. The more I heard about THAT, the better it sounded. No more straightening the computer book section at 10PM. No more counting out the cash register. Weekends off! In the fall of 1994, I got a job as a book buyer at B&T. I would be buying the new titles and reordering books for their warehouses. At first, I was given a handful of smaller presses to manage. I suppose they wanted to limit the damage I could do. I embraced the sales patterns of Michelin Travel Guides, Van Nostrand hair cutting manuals, and Latino fiction of Arte Publico Press.

Over the next four years, I moved on to buying more favorites that included Random House, FSG, Hal Leonard Music Books and Viking Penguin. The more I heard about the stories behind the books’ creation, the more interested I was. One of our reps recommended a new job at Holtzbrinck Publishers selling TSR. TSR? You mean Dungeons and Dragons? Yep. The game manuals and the novels. Game on. Why not?

I came into the Flatiron Building in New York on a hot May day in 1999. I misjudged the subway time, arrived late, and thought that walking up to the 12th floor would be faster than waiting for an elevator. I arrived sweaty, out of breath, and dis-shelved. Talk about making a good impression. I remembered how well those fantasy books sold back in the Welsh Road days and was hoping to be able to be a bigger part of their success “further up-stream”. I got the job and have since moved on to specialize in Children’s books. I feel very lucky to be working with such smart, creative, and fun people.

I occasionally go back to the mall near my parents’ house. Wee Three is gone. The Book End is gone. Encore is gone. The aprons are gone. Things change. But, storytelling and publishing always go on …

-

Global Publishing Sensation ‘Half Bad’ Sets New Guinness World Records Title

New York, NY – Exactly one year after clinching her first publishing deal, British author Sally Green has smashed two GUINNESS WORLD RECORDS titles for the ‘Most translated book by a debut …

-

Christopher Myers Talks About the Lack of Diversity in Children’s Books

“During my years of making children’s books, I’ve heard editors and publishers bemoan the dismal statistics, and promote this or that program that demonstrates their company’s ‘commitment to diversity.’ With …

-

CBC Diversity: Hiring Methods for a Representative Work Environment Panel

From the beginning, one of the goals of the CBC Diversity Initiative was to help create a more diverse range of employees working within the industry. Now in its third year, CBC Diversity is taking a closer look at how we can help bring about this change.

In February we attended a highly diverse college fair introducing qualified candidates to the many jobs in publishing. We plan to do more career fairs, virtual and in-person, in the future. This, however, is only one part of the equation.On March 12, 2014, the CBC Diversity Committee hosted a Lunch & Learn Panel for hiring managers and human resources professionals within children’s book publishing to come together and explore key ideas focusing on how to bring about a more representative industry. The amazing panel was moderated by Andrea Davis Pinkney, Vice President and Executive Editor of Trade at Scholastic, and the panelists included David Bronstein, Cheif Talent Officer at Perseus Books Group; Amy Brundage, Human Resources Director at Hachette Book Group; and Carolynn L. Johnson, Chief Operating Officer at DiversityInc.The takeaways were fabulous and below you’ll find just a few that were captured.

- The hiring manager is the key—understand their behavior, learn how to communicate with them, and educate them. This will have the best influence on who they hire.

- If you’re in the company, send referrals of candidates that you think would be great to HR. Those usually go to the top of the pile.

- It’s a numbers game. The companies who get it (that diversity is crucial to the bottom line) win, those who don’t go out of business. There is a business case for diversity.

- What makes a good mentee?

- A person who drives the mentorship process and comes to learn and engage

- A person that understands that it’s not all about the mentor giving to them, they should give back to the mentor as well in whatever way they can to add value to the relationship

- A person that understands that there’s a difference between a mentor, a sponsor, and a coach. Asking one person to be all of those things won’t work because they have different responsibilities and needs. It’s important for a mentee to always be networking so they have access to many advocates.

- Training is so important for hiring managers because it shows them that they may have unknown biases and then will help decrease those biases in the future.

- A way to infuse diversity training into the company is to do it within higher management training.

- Include two-way interaction with scenarios

- Try to provide a training session where the manager feels like they’ve solved 3-4 problems in the session (presumably through those scenarios)

- Companies have to do the work if they care about creating and promoting their diversity.

- Is it in the job posting description of the company? Where are you posting the job—just within industry-specific websites or only on the company website?

- Is there diversity on the company website?

- Where and how are your corporate values communicated and where does diversity fit in?

- Hiring managers need to go to where the people are—to the communities, individuals, institutions that have the diversity that you crave. They aren’t going to come to you—especially if the above bullet isn’t handled.

- Numbers are important. Ask managers to pay attention to those numbers because when you shine a light on something, there is change.

-

Fans Encouraged to Take Part in ‘The Great Daughter of Smoke & Bone Re-read’

“Other digital and social media components of the promotion include Facebook and Tumblr book giveaways, and a Daughter of Smoke & Bone Tumblr site showcasing fan-art as well as an …

-

Veronica Roth On Growing as a Writer

“In the subsequent books I thought more about violence and young people. It’s very serious. That doesn’t mean I’m limiting the content. I just handle it different. In terms of …

-

New Content From Author J.K. Rowling Posted on Pottermore.com

LONDON, ENGLAND – Pottermore.com, the digital platform from author J.K. Rowling devoted to the world of Harry Potter, today posted the first part of her “History of the Quidditch World …

-

Walter Dean Myers: ‘Where Are the People of Color in Children’s Books?’

“TODAY I am a writer, but I also see myself as something of a landscape artist. I paint pictures of scenes for inner-city youth that are familiar, and I people …

-

2014 Hans Christian Andersen Awards Shortlist

The Hans Christian Andersen Award Jury of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY) Announces the 2014 Shortlist Six authors and six illustrators have been selected from 58 candidates submitted …

-

Zareen Jaffery: How I Got into Publishing

Executive Editor at Simon & Schuster

The day I got my first interview in publishing, I was kind of a disaster. I really wanted to be an editor—or at that point, an editorial assistant. I wasn’t thinking as far ahead as editor since I could barely get my foot in the door.

From the outside, publishing can seem like an insular industry, where entry-level employees are hired based on who they know—whether through personal connections, internships, or a graduate level publishing course. And certainly, people do get hired via those methods. I had none of those things, and really worried that I wouldn’t be able to get hired because I wasn’t connected enough.

I’m one of those people who has a hard time asking for help, and really what I should have done is get in touch with my college professors—some of whom were published authors and undoubtedly knew editors and agents—and ask for introductions. My shyness kept me from doing that.

So I dutifully sent my resume to publishing houses and magazines (I was interested in both at that point) via their online job listings. I’d been temping at an investment bank in the HR department for several months, and there was a moment where I could have stayed on there full-time, but I knew that I needed to at least try to work in publishing, or I would always regret it. After all, I had a real love of reading, and nothing resembling even liking for either investment banking or human resources. Finally, I got two interviews scheduled for the same day: Scientific American magazine, and Harlequin.

The Scientific American interview was first. And, boy, did I bomb that interview. I was incredibly nervous, had put way too much pressure on myself, and ended up getting so tongue-tied, I was barely coherent.

When I left their office, I was pretty much in tears from being disappointed in myself. But I wiped those away and gave myself a Stuart Smalley-esque pep talk as I walked over to Harlequin.

And it worked! The interview went great and I left with a manuscript editing test which I knew I would rock. My first job in publishing became editorial assistant at Red Dress Ink, a division of Harlequin that was focusing on the then-burgeoning chick-lit trend.

From there, I moved around quite a bit—eventually moving from editing chick lit and romance, to a house that focused mainly on non-fiction and commercial fiction. About five years in to my publishing career I realized my real love was children’s books. This was not solely because of the Harry Potter phenomenon (though that helped!). My brother, who was in high school at the time, handed me a book he’d had to read for school that he thought I’d like. It was Laurie Halse Anderson’s Speak. I loved it. It was so exquisitely written and moving. So I started reading everything YA and middle grade I could get my hands on. And even ended up co-writing a YA novel with a friend of mine.

When a position opened up at HarperTeen, Farrin Jacobs, a friend and former colleague of mine from Harlequin was working there. I expressed interest and interviewed with several people before I got the job. My knowledge of (and enthusiasm for) the books that were being published, and networking with kids lit editors and agents, helped my case. What people don’t tell you about publishing is that more than half your job requires being social—this is an industry based on relationships. Those “connections” I had been afraid of before I started my career were more about having people vouch for your work ethic than about nepotism. And every job I’ve gotten since Harlequin, I’ve gotten the interview through people who I’ve worked with.

Also, in making the transition from adult books to kid’s book, I think it was tough to bring someone in who hadn’t “grown up” in children’s publishing. It really is a different world from adult publishing—though there is now more overlap thanks to so many adults reading YA fiction in the post-Twilight years.

Moving to children’s publishing was the best career decision I’ve ever made. There is something so special and rewarding about publishing books that may help spark a kid’s lifelong love of reading.

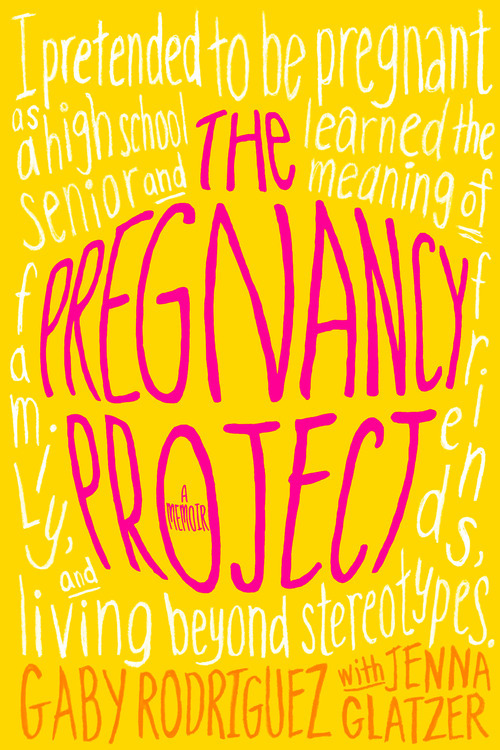

I’ve been at Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers for three years, and have had the opportunity to work on some amazing books. My role focuses on commercial fiction and non-fiction, so the books I bring in have to appeal to a wide audience. I’ve been lucky enough to work on several books that feature diverse characters, or are written by writers of color. Most recently, that list includes Octavia Spencer’s middle grade series, Randi Rhodes, Ninja Detective and the soon-to-be-published teen novel, To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han. And I’ve been honored to work on two memoirs, The Pregnancy Project by Gaby Rodriguez and Hidden Girl by Shyima Hall. I look forward to publishing many more!

-

Scholastic to Launch “Worlds Collide” Initiative Bringing Together Authors & Fans of Bestselling Multi-platform Series The 39 clues®, Infinity Ring®, & Spirit Animals™

New York, NY — Scholastic, the global children’s publishing, education and media company, and the pioneering publisher of the bestselling multi-platform series The 39 Clues®, Infinity Ring®, and Spirit Animals™, announces the “Worlds Collide” …

-

A Letter From the CBC and ECAR About the Children’s Choice Book Awards Finalists

Dear children’s literature community — We at the Children’s Book Council and Every Child a Reader sincerely appreciate your concerns about this year’s Children’s Choice Book Awards, and wanted to …

-

Diversity 101: The Multiracial Experience

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Monica Brown

In the 2013 Census, nine million people selected more than one race. In states like California, where I grew up, as well as Texas, and New York, half a million or more people, in each of these states, marked multiple-races. Yet when I became a mother of two beautiful daughters, Isabella and Juliana, I looked around and couldn’t find books that represented the multiplicity of our experiences as a family of two continents, many races, and diverse cultural traditions. We are a nation of boxes, and until the 2000 census, we could mark only one. It is unfortunate that many of our children’s books mirror only part of our culture and that many voices still go unheard.

My Personal Connection

My daughter, Isabella (named in honor of my mother Isabel Maria) was born in 1997 in Tennessee. We were living in a region of Tennessee where there were very few Latinos and race was defined in terms of black and white. In the hospital, the nurses informed me that they adored my daughter, with her shock of black spiky hair, and that they called her “our little Eskimo.” My own family said, “She sure looks like a Valdivieso!” and yes, with in her dark eyes, light olive skin and beautiful black hair, I saw the face of my mestiza Peruvian Grandmother. But she also shared roots in Jewish Romania and Hungary, Scotland, and Italy. From my husband Jeff, came Sweden, Norway, Ireland, and Germany. Surely a citizen of the world was born on that day in 1997.

“The little Eskimo” was the first box my Isabella was put in. Because if you look “ambiguously ethnic”(and here I borrow Sherman Alexie’s phrase), people want to place you.

Recently, my daughter’s teacher used her as an example during a class discussion of Nazi Germany, stating “Because of her global ethnic origins, Isabella is an example of what the Nazis would have classified as Negroid.” He then pointed out blond students as examples of what the Nazis would have called “Aryan superiority.” I am sure the teacher intended the exercise to illustrate the absurdity of white supremacy, but I am still struck by the ways my multiracial teen, and other ethnically diverse students, are still put in boxes and on display.

Terminology

There are many words associated with multiracial people, some negative and some positive. I prefer mestiza, because it encompasses both my European and Peruvian indigenous origins. But that’s technically (or at least historically) incorrect because while I have Spanish and Indigenous Peruvian origins on my mother’s side, I also have Eastern European Jewish, Western European and African origins. Some people prefer the terms “mixed,” others “biracial.” Of the choices available, I choose “multiracial.” President Obama has jokingly called himself a mutt, and there are other terms meant to be humorous that I feel uncomfortable with. Though I’ve described myself as “half Peruvian” or “half Jewish” as a shortcut in the past, I fully reject those terms now. I am not half of anything. I am whole in myself, as are my daughters. I am the Latina daughter of a Latina woman. I am bilingual. I am the face of a complex, multiracial, multilingual, and multicultural past, present and future. As with any other groups, we must respect and listen to how people choose to self-identify.

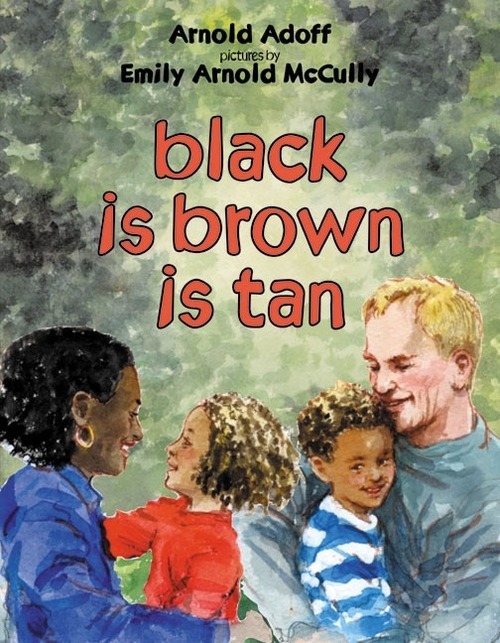

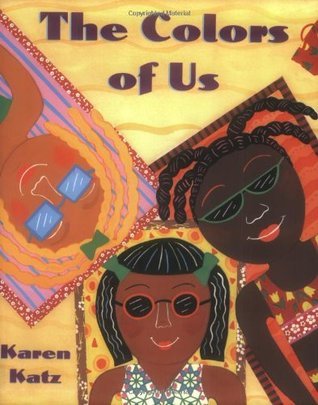

Great Examples to Follow

There are very few picture books representing the multiracial experience, and of those, most focus only on color itself, not culture, and stay at very surface levels. Books such as Black Is Brown Is Tan (HarperCollins 1973/ 2002), by Arnold Adoff, Black, White, Just Right (Albert Whitman & Co. 1993) by Marguerite W. Davol, and The Colors of Us (Macmillan 2002), by Karen Katz, and are lovely, representing joyful multiracial families. Black Is Brown Is Tan was the first picture book, to my knowledge, to depict a multiracial family. In the book, Adoff writes poetically:

black is brown is tan

is girl is boy

is nose is

face

is all

the

colors

of the race

Adoff also mentions the individual characters in terms of color:

granny white and grandma black

kissing both your cheeks

and hugging back

Similarly, Karen Katz’s young protagonist gets ready to paint her friends, and focuses on color: “I think about all the wonderful colors I will make and I say their names out loud. Cinnamon, chocolate, and honey. Coffee, toffee, and butterscotch. They sound so delicious.” The clear message is all colors are beautiful. In Black and White, Just Right, Marguerite Davol writes, “Mama’s face is chestnut brown. Her Dark brown eyes are bright as bees. Papa’s face turns pink in the sun; his blue eyes squinch up when he smiles. My face? I look like both of them—a little dark, a little light. Mama and Papa say, ‘just right!” The illustrations include smiling images and text to match.

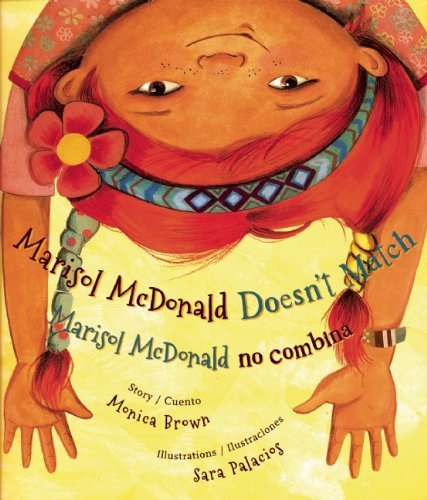

I respect these authors and publishers for putting positive images of multiracial families out there, because I know from personal experience just how difficult it can be to place these stories. Of my many published children’s books, my semi-autobiographical story Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match/Marisol McDonald no combina (Lee and Low, 2011), illustrated by Sara Palacios, received the most rejections from publishers, which is ironic as it has resonated both critically and with children across the nation, winning multiple awards and starred reviews. It is now in its fifth printing!

Marisol McDonald is the daughter of two cultures and two languages who sometimes gets teased for being different. Her story affirms the power of being oneself. Marisol claims and redefines the idea of being “mismatched” and makes that label something marvelously her own. In the sequel Marisol McDonald and the Clash Bash/Marisol McDonald y la fiesta sin igual (Lee and Low, 2013), Marisol turns eight and continues to celebrate her individuality, while grappling with missing her Abuelita, who can’t get papers to visit from Peru.

What I’d Like to See

I participate in book festivals and visit schools all over the country, and everywhere I go, I meet children who tell me, “I am Marisol McDonald!” and “She is me!” This doesn’t mean that they have olive skin and red hair, or that they are Peruvian and Scottish. Rather these exclamations of joy mean that young readers see themselves in this girl whose ethnic diversity and unique choices do not divide her, but makes her beautifully whole.

Children don’t see themselves in boxes. I think we are ready for more diverse and realistic renditions of the joy (and challenges) of the multiracial experience in our children’s picture books. Our children are beautiful blends of many cultural traditions, with roots and history here in the United States, as well as Africa, Asia, Native America, Latin America, Europe, and the Middle East. We are bilingual, multilingual, and our families’ religious traditions may also be diverse. It’s time that our children’s literature holds up a mirror that has room for all our reflections.

Monica Brown, Ph.D. is the author of more than a dozen picture books, including, Tito Puente: Mambo King/Rey del mambo, which won a Pura Belpré Honor for Illustration, the Christopher Award-winning Waiting for the Biblioburro, and the NCTE Orbis Pictus Honor book Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People. Finally, she is the author of the Marsiol McDonald series. Monica Brown will be speaking and signing her books at the Texas Library Association Conference in April 2014. Find out more about Monica at www.monicabrown.net or like her author page on Facebook.

-

#1 New York Times Bestselling Author Scott Westerfeld to Publish a New YA Novel with Pulse

NEW YORK – Pulse, an imprint of Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing, has announced today that Afterworlds, a young adult novel written by Scott Westerfeld, will be published on September 23, 2014. Scott …

-

Voting for the 7th Annual Children’s Choice Book Awards Opens March 25, 2014!

The only national book awards program where the winners are selected by children and teens. Last year, over 1,000,000 votes were cast by young readers! This year’s finalists …

-

The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art Seeks Public Submissions for its ‘What’s Your Favorite Animal?’ Exhibition

Amherst, MA — The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art is creating a special exhibition to celebrate the new book What’s Your Favorite Animal? by Eric Carle and Friends. The Museum will showcase …

-

Laney Nielson Wins Cynthia Leitich Smith Mentor Award

“Laney’s manuscript, ‘Shattered,’ was chosen as the winner due to its charm, humor, and kid appeal,” said Cynthia. “The quality of finalists’ writing, obvious potential, and wide variety of their …

-

Children’s Authors Participate in the Twitter Fiction Festival

The organizers also plan to host the #TwitterFiction Festival Live! event in New York City. R.L. Stine, a prolific children’s horror author, will join in for a night of storytelling. …

-

Harriet and Scout: “How To Be a Good Bad American Girl”

“The story of a six-year-old girl observing the oppressive racial politics of the fictional Maycomb, Alabama, in the nineteen-thirties may not seem to much resemble that of a sophisticated, eleven-year-old …