CBC Diversity 101: Blurring the Lines Between Familiar and Foreign

Part I—A Focus on Narrative

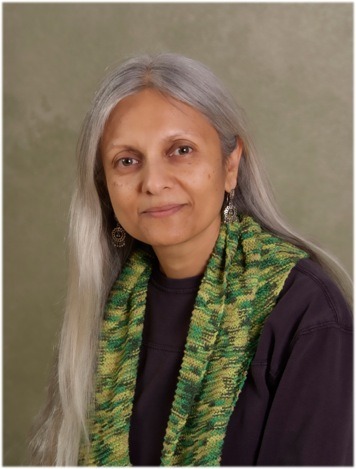

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Uma Krishnaswami

Back in the last century, when I dreamed of writing for young readers, the conventional wisdom about weaving foreign languages into fiction written in English went like this:

Don’t.

The stories I longed to write spanned continents. My characters often spoke in two languages, sometimes with varying degrees of fluidity. My narratives demanded a mixing of languages, reflecting the hybridity I was trying to show.

I plunged in, wanting to find my own answers. I wrote a lot of bad stories that earned the rejections they deserved. I kept asking myself, how can I represent this linguistic and cultural material while being truthful to the stories I’m trying to tell?

Over the years, I’ve tried many ways of weaving in snatches of the languages of India into the narrative in my books. I’ve settled on a few guidelines that make sense to me:

- Avoid stepping out of the story to translate a word or phrase. Instead try to make it clear in context.

- Avoid parenthetic comma phrases. More on this in this 2009 blog post, Parenthetic Comma Phrases, Anyone?

- Read the work aloud and listen—really listen—to it. Is there meaning constructed from the linguistic overlaps that would be missing without it?

- Trust the reader.

I want to emphasize that this is about narrative, not dialogue. Sprinkling foreign languages in dialogue—that’s for another conversation.

Revisiting this subject now, I thought of books I’d loved in my childhood and teenage years—books that seemed to whisper to me confidentially, as if they’d been written for me alone. Was there something to be learned from revisiting those texts?

To find out, I took a look at two texts that were formative in my young reading life: The River by Rumer Godden, and “Rikki Tikki Tavi,” from Kipling’s The Jungle Book.

Here is a passage from The River in which young Harriet, living in India, is battling with Latin declensions. Talk about hybridity!

It is strange that their first Latin declension and conjugation should be of love and war:—

Bellum Amo

Bellum Amas

Bellum Amat

Belli Amamus

Bello Amatis

Bello Amant

“I can’t learn them,” said Harriet. “Do help me Bea. Let’s take one each and say them aloud, both at once.”

“Very well. Which will you have?”

“You had better have love,” said Harriet.

There is no translation. Sufficient that the subject is love and war. The Latin words are a litany of opposing forces. They can be thought of as music. Literal translation is irrelevant. In a sense, the lyrics are yet to come, in Harriet’s own story of longing and ambition, carelessness and betrayal. Elsewhere in The River, Godden scatters words like bazaar, ayah, and Diwali, un-italicized, trusting readers to understand them contextually. To contemporary readers, they may be no more alien than English words like bauhinia and jute. Most importantly, Godden limits the mixing of languages to suit her young viewpoint character’s perspective. European in India, Harriet would be privy to some elements of local language and culture but not others.

In “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi,” Rudyard Kipling names his animals with Hindi descriptors:

This is the story of the great war that Rikki-Tikki-Tavi fought singlehanded, through the bathrooms of the big bungalow in Segowlee cantonment. Darzee, the tailor-bird, helped him, and Chuchundra, the muskrat…

By ducking the need for translation, the narrative creates the illusion that all readers are privy to a hybrid English in which animals have names—itself a conceit—and those names are borrowed easily from the subcontinent. Illusion, in fiction, is everything.

In “Toomai of the Elephants,” Kipling relies more upon the narrative conventions of his time:

Kala Nag, which means Black Snake, had served the Indian government…

His mother, Radha Pyari—Radha the darling—who had been caught in the same drive…

Both stories boast a strong narrative voice, but the little mongoose’s journey is far more compelling.

Surprisingly, we still seem to rely upon Victorian conventions of parenthetic translation. But there are alternatives.

Look how the word “pakora” occurs in the opening pages of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s novel, The Conch Bearer:

“…maybe, thought Anand with a grin, it was just his boss, Haru, the tea stall’s owner, frying onion pakoras once again in stale peanut oil!”

Later:

“The smell of the hot pakoras he was carrying was driving Anand crazy. He was so hungry! He had to clench his teeth hard to resist the urge to sneak a pakora—just one—into his mouth.”

We’re engaged by sensory markers like food smells, clenching of teeth, and hunger. Defining the pakora is beside the point.

- In The Wild Book, Margarita Engle scatters words like reconcentración, indio, guajira through delicate verse stanzas. She uses italics but clarifies contextually and without sacrificing rhythm and pacing.

- Rickshaw. Longyi. Mua. Peh. These few words serve to pin the Burmese setting in place in Bamboo People by Mitali Perkins.

- In Kashmira Sheth’s The No-Dogs Allowed Rule, the first person narration invites the reader to engage with the family’s food, habits, and culture, with Hindi words thrown in like dashes of turmeric.

These books would not be the same without their linguistic blends. Hybridity seems best achieved when the dream world of the story is maintained, when the author’s intention is not overly visible, when the writer trusts the reader enough to resist the impulse to explain everything.

Uma Krishnaswami is the author of The Grand Plan to Fix Everything and The Problem With Being Slightly Heroic, both from Atheneum Books for Young Readers.