CBC Diversity: A Conversation with Tanya McKinnon

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Wendy Lamb

I wanted to interview Tanya McKinnon for this blog for a number of reasons— she’s such an inspiring and generous member of the publishing community; she’s an agent, and the co-author of the acclaimed middle grade novel Zora and Me; she’s both eloquent and realistic on the topic of diversity; and and I wanted to hear more about her course at CCNY where she teaches Writing for Children within the publishing program.

Wendy Lamb: Tanya, you’re an agent, an author, a college instructor, and you have a masters in cultural anthropology. There so much we could talk about. Let’s start with agenting—what kind of books are you looking to represent?

Tanya McKinnon: As an African-American agent with a diverse client list in both children’s and adult books, I am always on the lookout for books that push the envelope of human understanding. Books that honor our multicultural world, regardless of who writes them, are my passion.

WL: Why did you decide to teach Writing for Children in the Publishing Certificate Program at City College?

TM: I love teaching; one of my favorite ways to spend an afternoon is opening students to the wonderful complexity of children’s books. The students at City College have changed over the nine years I’ve been teaching there, but what has stayed constant is their hunger for works by and about people of color. I look for fiction that feels unselfconsciously racially inclusive, such as Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Saenz, I Hadn’t Meant to Tell You This by Jacqueline Woodson, and When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead, just to name the first titles that come to my mind.

I also love teaching because I’m a social introvert and I’m selfish and I like learning things. Every semester my students teach me new things about the books we read and the process of learning to write. I think we all teach to learn.

WL: You said that one important focus is: why diversity—why are we so compelled by it?

TM: I have come to believe that we say diversity as a placeholder for more emotionally difficult concepts, like hegemony, invisibility, and hate. The problem of diversity is most often a problem of hate: both the fear of feeling hated by others and the hate we carry inside ourselves—that part of ourselves and our cultures that is most intolerant. We care about diversity because we fear the repercussions of hate.

Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman’s NurtureShock: New Thinking about Childhood, makes it clear that even when parents think they are providing a tolerant and diverse environment for their child, if they don’t talk openly about race and ethnic difference, the child can have racist attitudes by the age of five. Five! That’s so young – it’s an age when well-intentioned parents are still trying to shield their children from the knowledge of hate-driven differences like racism. Yet if we think of hate as the sharpened edge of unexamined stereotype, not talking about it becomes a way of teaching children to take on the negative feelings and assumptions from the culture and – however unarticulated – their own home.

According to neurological research, the thing that reduces hate and increases acceptance of diversity is knowledge and rational thought. The more we use our pre-frontal cortex, the seat of rational thought, the more likely we are to reduce hate. That’s why reading about difference, especially at a young age, is so very important. And it’s why racially inclusive children’s books are so crucial for a rational and tolerant society.

WL: I hope some of your students will end up as editors. What must publishers do to attract and retain diverse staff?

TM: For a long time, as you know, careers in publishing and other elite forms of professionalized art were the province of the privileged. I, for instance, graduated from college in the late 80s with an English degree and the desperate desire to live and work with books. I was lucky to have a powerful academic mentor who was also a writer; she introduced me to the world of book editing. My first job in publishing was as an editor at South End Press in Boston. Without that mentor, I may not have found my way to publishing.

Young people from working class backgrounds, and especially young people of color, may never have met a book editor. They may not know the career even exists. This is why exposure is one of the key ingredients in attracting talented young people of color. That, and a salary they can live on!

TM: Now I have a question for you. How do you think reading about “others” effects change?

WL: If a work reaches readers in a true emotional way. Sensitivity toward, and curiosity about, someone who is different from you can begin early in response to strong, well written books.

TM: As an editor, do you think “monitoring” who gets to write about race, and the notion that writers can only write about their own groups, helps or hinders diversity in publishing?

WL: It hinders diversity and creativity. “Monitoring” can intimidate writers so that they don’t feel free to pursue certain topics, or to tell a story from a point of view that is not their own. It can make editors and writers pull back from exploring complex new territory because it’s easier to stick with what you know, and what’s been welcomed in the past.

I tell authors: “You can write anything you can fully imagine. If you write outside your group or your experience you may be criticized. So, prepare for that. But first—write the best book of your life! Research it deeply; consult people from that community, that world. Use an afterword to discuss your research, establish your intentions, and your credentials. Make it clear that this book was created with care, respect, and passion. My colleagues and I will support you all the way.”

I know you also feel it’s important to encourage writers who feel intimidated about writing outside their own ethnicity.

TM: I spend a good portion of every semester getting my students to embrace all the possibilities of empathy and identification that fiction writing allows. In fact, I require them, regardless of whether they identify as writers or not, to write a first chapter and full synopsis for a middle grade novel and a YA novel. I tell them not to worry – that people who love writing but are not themselves writers make great editors, precisely because they understand how relentless the task of self-interrogation must be to produce believable and compelling characters on the page.

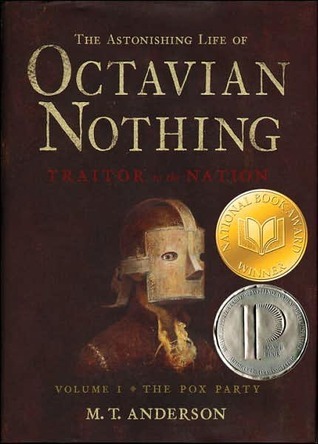

I also teach The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, by M.T. Anderson. I teach it for many reasons, but one is to show my students that race is no impediment to human understanding. That novel, both volumes, is a masterpiece; no black person could have written it better. It is proof that, even as we desperately need new voices of color, we should never succumb to shallow literary nationalism.

Diversity is such a tricky subject, and it makes everyone so nervous. When my class reads Marc Aronson’s Race: A History Beyond Black and White for our non-fiction section, I tell my students this: “I would much rather you make a mistake with me because you’re trying to break through received ideas of race, class, gender, orientation, nationality, religion, than that you remain quiet and safe and miss the beautiful opportunity of experiencing your full humanity.”

I think that reaches them. My hope is that they always dare to reach each other.

Tanya McKinnon is an agent with McKinnon-McIntyre, a writer, and teaches the Writing for Children in the Publishing Certificate Program at City College. She has a master’s degree in cultural anthropology. Under the name T.R Simon, she wrote Zora and Me with Victoria Bond. This delightful middle grade novel was inspired by the early years of Zora Neal Hurston, and won the John Steptoe New Talent Author Award.