Dumpster Diving: An Observation on Class in Children’s Books

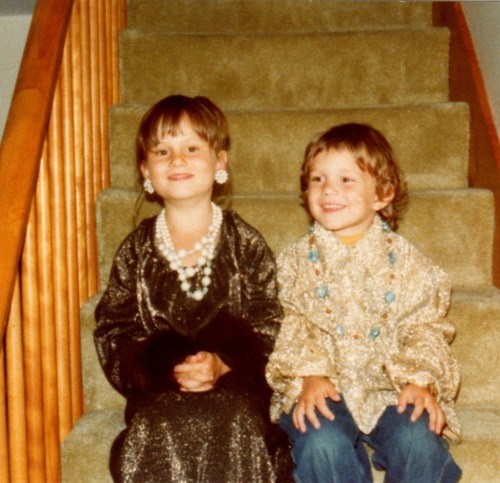

When my sister and I were kids, we used to play next to (and sometimes on) the dumpsters in the parking lot while my mother cleaned offices. At the age of twenty-two, my mom was a single parent of two small children, putting herself through college while working as a waitress and cleaning lady. We were on food stamps and participated in WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) and AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children). I had free lunch at school. Welfare paid for our childcare so my mom could work and take classes, and somehow, we managed to squeak by.

Eventually my mom graduated and took a job as a teacher, and things improved. They improved even more when she remarried and we became a two-income household. My lunches went from free to reduced-price. And by high school I paid top dollar for my soggy pizza and curly fries and had an allowance of three dollars a week. Which wasn’t half bad in the 1980s, all things considered.

Eventually my mom graduated and took a job as a teacher, and things improved. They improved even more when she remarried and we became a two-income household. My lunches went from free to reduced-price. And by high school I paid top dollar for my soggy pizza and curly fries and had an allowance of three dollars a week. Which wasn’t half bad in the 1980s, all things considered.

I was a smart kid and did well at school. I got a generous financial-aid package to attend Harvard and found myself living in the Yard, taking classes from future and former US Cabinet officials when I was the age my mom had been when she was cleaning offices and struggling to put food on the table. I was surrounded by private school kids and legacy students. To say I experienced culture shock is putting it mildly.

So yeah, class interests me. I care a lot about public assistance to the poor, and I have some insight into the problems of working single parents and their children.

But oddly enough, I haven’t brought that focus much into my work as a children’s book editor, even knowing firsthand how powerful books can be for the disadvantaged. Once I sallied forth from Cambridge, Ivy League diploma in hand, I kind of forgot about my roots.

I was reminded of these roots recently, however, when the CBC hosted a diversity workshop here in Boston. Cathryn M. Mercier, Director of the Center for the Study of Children’s Literature at Simmons College, taught a three-hour “class on class.” The following is from the registration information:

This workshop will examine how class appears, or as sociologist William Julius Wilson claims, disappears, in literature for children and young adults. In an intensive, hands-on session, participants will learn how to read class by exploring the following questions:

- Where is class indicated in books?

- Where or how do we ignore the class indicators that are there?

- What kind of diversity does class status constitute and why should we care?

- What kind of other myths (power, visibility, inclusion, representation) are covered by the stories we tell about class in the stories we tell to our children?

The workshop content is proprietary, so I can’t get into the specifics of what we read and how the class was structured, but I can report that it was a lively discussion among colleagues. The attendees were mostly fellow publishers, many of whom were graduates of the Simmons children’s literature program. We examined middle-grade, YA, and picture books.

One strategy I’ll take with me into my editorial work is to look more carefully and deliberately for class markers and where they appear or don’t appear in text and art. Indeed, the latter is an intriguing issue to explore in any book: who is NOT in a given story, and why? Other questions that came up for me:

- Is it possible that when I edit a text for clarity and brevity, I might be stripping out class markers that the author has included? (Keep in mind that most of my editorial cuts happen well before an illustrator gets to see the text.)

- What effect does propagating a middle-class norm have on children either above or below that “normative” level? How important is it for children to see themselves in a book, and how does that affect their enjoyment of the title?

- Isn’t “middle class” a rather imprecise catch-all anyway? What do I mean by “poor”? “Middle class”? “Rich”?

- How can I better balance the natural impulse to show kids a better (easier/simpler) world with the need to teach them about the one they live in right now?

- Is it possible to separate class from other labels such as race and gender?

- Can I work harder to understand how my unconscious ideology and the author and illustrator’s unconscious ideology are influencing the book?

- Aside from encouraging artists to explore non-suburban settings and on occasion to depict an apartment building instead of a single-family home, what more could I be doing to normalize different socio-economic realities in the books I help shape?

I have no answers. Just questions. But the point is that I’m examining my role and my unconscious biases. By looking and seeing what’s actually there, change can be effected.

I got my first pair of glasses when I was in second grade. We were still poor, so I have no idea how my mother afforded them. I imagine yet another government program came to our aid. I’ll never forget looking up at the trees around the playground and seeing individual leaves where there had only been a shaggy green blob before.

When we consider how class, race, gender, culture, physical ability, religion, and sexual identity appear in children’s literature, we have to consciously remind ourselves to put on our proverbial glasses so we can see the full spectrum of human experience and include it in the books we make and give to our children. Looking at the world this way, we might even see kids playing in dumpsters.

Yolanda Scott is editorial director at Charlesbridge, where she has worked since 1995. She is a co-founder of Children’s Books Boston and a former executive board member of The Foundation for Children’s Books, as well as a member of the CBC Diversity Committee. She lives near Boston.