Month: October 2014

-

Announcing YALSA’s 2014 Teens’ Top Ten

Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell (Macmillan/St. Martin’s Griffin) Splintered by A.G. Howard (ABRAMS/Amulet Books) The Rithmatist by Brandon Sanderson (Tor Teen) The 5th Wave by Rick Yancey (Penguin/Putnam Juvenile) Monument 14: Sky on Fire by Emmy …

-

Pearson Foundation Selects Groundbreaking Nonprofit to Receive Digital Platform and $1.3M

Press Release First Book to Harness Power of We Give Books on Behalf of Children in Need WASHINGTON, October 20, 2014 – First Book today announced a significant new commitment …

-

CBC Diversity: “Here I Am!”

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Brian Pinkney

When I was ten years old, my mom and dad made me my very own art studio. Actually, the “studio” was a walk-in closet that my parents converted so that I could have a place to call my own. It was the perfect spot for expressing my creativity without interruptions. (As one of four children, finding time to myself wasn’t always easy.)

As a budding artist, I wanted to grow up to become a children’s book creator, just like my father, illustrator Jerry Pinkney. Watching Dad, I was very fortunate to see books in which black children were front-and-center. Seeing Dad’s characters showed me, me. And it established a simple truth ― black kids in books were beautiful and could be rendered abundantly.

Following in Dad’s footsteps, I spent hours in my little workspace drawing all kinds of pictures. I also read lots of books, and dreamed big. Looking back, I realize now that my junior studio was a kind of retreat where I could pore over the pages of picture books. These books and their illustrations had an impact on how I perceived myself as an African American kid.

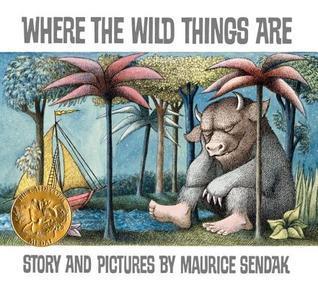

I also escaped to the studio so that I could enjoy all kinds of adventures that bubbled up in my imagination as I wrapped myself in books such as Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak. It didn’t matter to me that Max, the kid in Where the Wild Things Are, wasn’t black. He was me, and I was him. I saw myself through his adventures, not through his skin color.

Also, having observed my father’s depictions of black children, while at the same time loving books with all kinds of characters, gave me the gift of seeing picture books through two lenses ― the experiential and the cultural.

With so few picture books that included black characters like Max in Where the Wild Things Are ― kids who were having fun, embarking on adventures, pushing past authority, and exploring unchartered forests ― I was made to straddle two worlds: the universe of just being a kid and the land of being a black boy. Because I saw so few black kids in picture books who were like Max (and, who, through their adventures, were like me too), I was plunged into a syndrome that I’ve come to call “Where Am I?”

It’s been said many times, but can’t be stressed enough. Here’s how “Where Am I?” manifested in my world:

- As an African American kid growing up in the 1960s, there were very few books that reflected my experience.

- There weren’t many books that depicted boys who looked like me embarking on new discoveries, in the same way Sendak’s Max had done.

- By not seeing myself represented in books in these ways, I began to feel like a nonentity ― like the hole in the doughnut. I constantly asked, “Where am I?”

Seeing my father’s work showed me that, like my Dad, I could be the one who could someday give black kids images of themselves in books that reflected universal experiences. As a fourth grader, I didn’t walk around pounding my chest claiming to change the world through my art. Instead, I made a quiet, conscious choice. And as I grew as an illustrator, I stepped into that choice by deciding that the books I wrote and illustrated would do more than simply depict kids of color. I set an intention. Through my picture books, I would change “Where Am I?” to “Here I Am!”

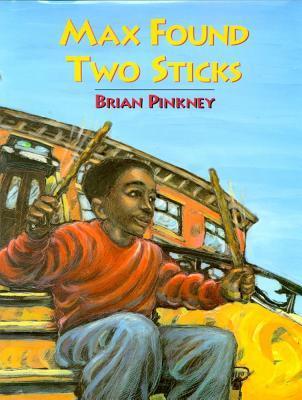

I started with a Max of my own creation. In my debut book as an author/illustrator, entitled Max Found Two Sticks (Simon & Schuster), young Max has limited language ability. Instead of talking, he expresses himself through the drumbeats he plays on the objects found in his urban neighborhood. Through Max’s own musicality and kinetic intelligence, he expresses his creativity and brilliance to everyone he meets. There’s also a magical realism element to the story. Not once is there mention of Max’s racial identity or ethnicity. He’s any kid and every kid who discovers his power through his own unique form of self-expression.

Max Found Two Sticks is one of my best-selling titles to date, and it has been embraced by kids and parents for its ability to empower readers of all types and abilities ― kids who struggle with reading and language; kids who are creative; children on the autism spectrum; and those who perceive their world through sound.

Max Found Two Sticks showed me something important, as it relates to diversity. I discovered that by empowering black characters, I was empowering all kids. This would seem obvious, but to many, it’s not. There’s still an assumption that picture books with black kids (especially black boys) as their central characters, can only appeal to a limited segment of the population. That showing a black boy front-and-center on a picture book’s cover, means that book is “for black boys only.”

It was an uphill climb to gain “crossover success” for Max Found Two Sticks. But it happened after years of me presenting the book at school visits and literacy conferences, where young readers and adults began to look past the book’s cover to its universality.

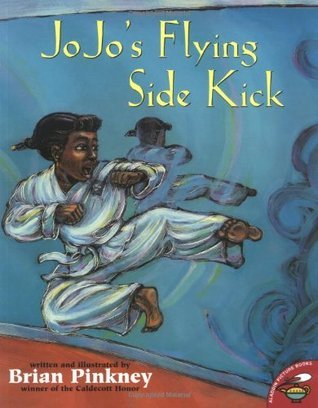

The same has been true of a picture book that I wrote and illustrated, entitled Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick (Simon & Schuster) about a girl who finds her own inner strength when she aces a martial arts test. The book’s cover shows high-flying Jo-Jo, who is African American, performing her best Tae Kwon Do maneuver. My intention with Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was to take the “Here I Am!” ideal to even greater heights. But I soon learned that the book had two strikes against it, in the eyes of some readers. People assumed that Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was a book for either Asian kids or black kids only ― until they read it, and saw that, like every child, everywhere, Jo-Jo faces, and overcomes, some of her worst fears. For reasons similar to Max Found Two Sticks (the limited perceptions of viewers who choose books by cover images), Jo-Jo’s Flying Sidekick was a slow build. But in time, the book turned into one of my strongest sellers, often purchased by parents, kids and teachers who are not of color.

I’m now embarking on a new book, entitled On the Ball (Hyperion/Disney Publishing, Fall 2015) that employs some of the same elements as my previous books that I’ve both written and illustrated. The story is told in minimal text. A curious boy chases after a lost soccer ball, and finds mystical animals, as well as his own hidden talents.

As a renderer of images that affect children, it’s essential that I stick to my commitment of showing black kids in all their glory. By doing this, I hope to be able to bring power, change, healing, self-expression, and heart to children of every color.

For anyone who reads and shares picture books with children, here are some tools that are helpful in moving past “Where Am I?” ― and making “Here I Am!” the way of our world:

- Cover Conversations: Before even opening a book, engage a child in a discussion about its cover by saying, “Wow, look at that boy on the front. He’s got drumsticks in his hand. What do you think this story is about?” And then inviting the reader open the book to find out more.

- Make it Personal: Ask a kid, “What are some of the things in this story that are similar to your own life, family, school, dreams, plans, etc.?

- Teachers Teach: Insist that your child’s teacher or school librarian always, under all circumstances, include books during story times and in classroom libraries that include people of color. Most folks are well-intentioned, but sometimes forget.

- Sail Away: Let a book’s story drive a child’s interest, rather than the color of its characters. Invite kids to create their own adventures based on the book’s themes.

Brian Pinkney is a two-time recipient of the Caldecott Honor medal and a New York Times bestselling illustrator. He was named one of the “25 Most Influential People in Our Children’s Lives” by Children’s Health magazine. To learn more about Brian Pinkney, visit www.brianpinkney.net.

Brian Pinkney is a two-time recipient of the Caldecott Honor medal and a New York Times bestselling illustrator. He was named one of the “25 Most Influential People in Our Children’s Lives” by Children’s Health magazine. To learn more about Brian Pinkney, visit www.brianpinkney.net. -

Meg Wolitzer Defends Adults Who Read Y.A.

“In fact, there’s just far too much variety in Y.A. to define it or dismiss it, and I don’t feel obliged to cast off my teenage reading habits as if …

-

Scholastic Turns 94

“Today (94 years later), 80% of K-6 classrooms in the United States read Scholastic classroom magazines each month. The 28 magazine titles, which include Scholastic News, Junior Scholastic, MATH, Scope, …

-

We Need Diverse Books to Launch the Walter Dean Myers Award

Grant winners will receive anywhere from $2,000 to $5,000 each depending on how much money is obtained through fundraising ventures. The organization will be running an Indiegogo campaign on October …

-

Lena Dunham Will Produce a Film Adaptation of ‘Catherine, Called Birdy’

The book is set in medieval times. The lead protagonist, a young girl named Catherine, shares her story through diary entries. Cushman won a Newbery Honor for this book in …

-

Millennials Surpass Older Generations in Reading Frequency

“Some 88 percent of Americans younger than 30 said they read a book in the past year compared with 79 percent of those older than 30. At the same time, …

-

YALSA’s 2015 Summer Reading/Learning Program Grants

Thanks to funding by the Dollar General Literacy Foundation, twenty $1,000 grants will be awarded to libraries to help update their teen reading collections. Another twenty $1,000 grants will support …

-

2014 National Book Award For Young People’s Literature Finalists Announced

2014 National Book Award For Young People’s Literature Finalists Threatened by Eliot Schrefer (Scholastic Press / Scholastic) The Port Chicago 50: Disaster, Mutiny, and the Fight for Civil Rights by …

-

Macmillan to Publish Lane Smith’s Debut Middle Grade Novel

Roaring Brook Press, an imprint of the Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group, will publish the novel on May 05, 2015. In an interview with Parade magazine, Smith talks about the inspiration …

-

Diversity 101: Asians as the Model Minority

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Janet Wong

When we look at the spectrum of racial stereotypes, Asians seem to have it good: We’re supposedly smart, hard-working, and obedient. We never complain. Families stick together. We don’t rock the boat (especially the fresher off the boat that we are).

What’s the Problem?

As far as stereotypes go, we’re pretty lucky. Some would say blessed. Who wouldn’t want to be prejudged as all those positive things?

For starters:

- the amazing Japanese child who is dismissed as “just the typical Asian whiz kid”;

- the B student who is considered an “embarrassment” to his Chinese parents;

- the Korean teen who “brings shame” by getting a tattoo;

- the Asian family of divorce.

The problem with all stereotypes—racial, cultural, gender, whatever—is that they interfere with your ability to be seen as you. You want to play football, but the Model Minority Stereotype (MMS) says: “Try the marching band.” You want to be a hip-hop star, but the MMS says: “Math and science.” Or maybe you need help, but are unable to reach out. The MMS says: “Asians are quiet. She’s perfectly fine.”

The MMS in Children’s Books

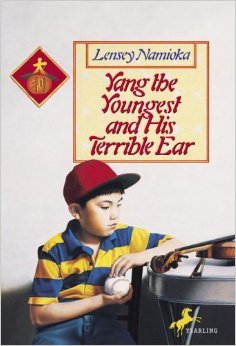

Many Asian American children’s books have used the MMS as a familiar point of departure. It’s a clever device that urges readers to look more carefully at Asians they know in real life. We show you what you expect—and then we turn the MMS on its head. Lensey Namioka’s Yang family is full of talented musicians but, in Yang the Youngest and his Terrible Ear, Yingtao is a musical dud who “bow-syncs” his way through a recital. Lenore Look’s Alvin Ho is quiet and timid at school, but he’s loud and rowdy at home. Lisa Yee’s Millicent Min is a Chinese genius, but her equally-Chinese Stanford Wong is an F student. In David Yoo’s The Detention Club, Sunny Lee is a brilliant overachiever “queen bee,” but she hides a terrible, definitely-not-MMS, secret.

My Own Work

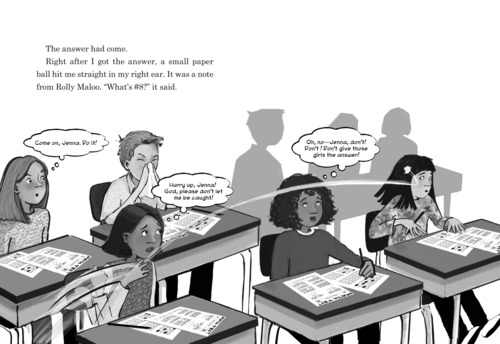

The MMS has made appearances in my own work, too. In the chapter book Me and Rolly Maloo, 4th grader Jenna Lee is great at math, socially-isolated, and eager to find a friend. These traits make her an irresistible target for Rolly and Patty, who use her to cheat on a standardized test.

But wait: is Jenna Lee Asian? I never say so in the book. Opting for a post-racial view of things, I chose not to give the characters in Me and Rolly Maloo definitive racial or ethnic identifiers. Lee is a wonderfully ambiguous surname, one that could be Asian (Ang), black (Spike), or white (Jennifer, director of Frozen). I left the choice of race to illustrator Elizabeth Buttler (elizabethbuttler.com), who decided to depict Jenna as Asian or part-Asian; Principal Young as Asian; Shorn L. Loop and Rolly Maloo as black; and all other named characters as white.

There’s a video going around with a couple having an argument over what to have for dinner:

“What do you want?”

”Anything.”

”OK, pizza.”

”Anything BUT pizza!”

Sometimes you don’t know what you want until you encounter something you don’t want. I didn’t want to have to assign races in my text, but I wasn’t sure about Elizabeth’s choices either. The Rolly character is a popular and clever rich girl but also a weak math student and the co-instigator of the cheating. No race would be proud to claim her, so my visceral reaction was: “Default to white!” Which Elizabeth did with the other instigator Patty, perhaps the most evil of all the characters in the book (after her PTA princess of a mom). But Rolly is shown as black. Could we do this to black children? The MMS is a burden, yes, but it’s mainly a positive burden, like carrying a hundred-pound box of books around school. Black stereotypes are a five-hundred-pound bag of manure; I did not want to add to that.

I asked my editor if it might it be better to have the strong math student (Jenna) be black or Latina; the weak-in-math and evil students (Rolly and Patty) be white and Asian; and the weak-in-math but kindhearted students be something else. If the chief instigator were Asian, wouldn’t that play into the very negative stereotype of Asians as cheaters (think “cheap designer knock-offs”)?

Midway through I asked: how about if everyone simply looked mixed-race, as we might in a few generations? I took the mixed-race route in Minn and Jake, not referencing Jake’s ethnicity at all in the first book, where it was irrelevant—but then identifying him as one-quarter Korean when introducing his Korean grandmother in the sequel. We decided that this would be too convenient here. Difficult as our choices were, it was better to make them.

In the end we all agreed that the villainous black (or possibly Indian?) Rolly Maloo was successfully offset by the courageous, spunky, funny hero Shorn L. Loop. Kids would hiss at (white) Patty but cheer for (white) Hugo. Asian Jenna, a math whiz, plays into the MMS but there are indeed many Asian children who are good at math.

What I’d Like to See

If the whole process above sounds borderline ridiculous, you’re right; it felt that way at times. But only because this kind of conversation is still the exception. I wish that all authors, illustrators, editors, and art directors would start insisting on this kind of discussion before a single child is drawn. Even if a book’s characters are “default-white”—that, too, should be made as a conscious and reasoned choice. Let’s turn these stereotypes on their heads, a book at a time; talk is a good place to start.

Asian American MMS-Busters Mentioned

Look, Lenore. The Alvin Ho series; first book: Alvin Ho: Allergic to Girls, School, and Other Scary Things (Schwartz & Wade/Random House, 2008).

Namioka, Lensey. The Yang family series; first book: Yang the Youngest and His Terrible Ear (Joy Street, 1992).

Wong, Janet. Me and Rolly Maloo (Charlesbridge, 2010).

Wong, Janet. The Minn and Jake series; first book: Minn and Jake (Frances Foster/FSG, 2003).

Yee, Lisa. Millicent Min, Girl Genius (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, 2003).

Yee, Lisa. Stanford Wong Flunks Big-Time (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, 2005).

Yoo, David. The Detention Club (Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins, 2011).

Janet Wong (janetwong.com) is the half-Chinese, half-Korean, sometimes MMS-y, sometimes-not, half-poet, half-prose author of two dozen books including Me and Rolly Maloo, a Horace Mann Upstanders Honor winner. She is also the current chair of the IRA Notable Books for a Global Society (NBGS) committee.

Janet Wong (janetwong.com) is the half-Chinese, half-Korean, sometimes MMS-y, sometimes-not, half-poet, half-prose author of two dozen books including Me and Rolly Maloo, a Horace Mann Upstanders Honor winner. She is also the current chair of the IRA Notable Books for a Global Society (NBGS) committee. -

Looking For Alaska Special 10th Anniversary Edition in 2015

New York, NY – Penguin Young Readers is pleased to announce the release of a special tenth anniversary edition of John Green’s LOOKING FOR ALASKA. Soon to be a major motion picture, …

-

Constantin Film to Develop ‘The Mortal Instruments’ as a Drama TV Show

“Constantin had originally planned to turn Clare’s fantasy series into a feature film franchise but shelved that idea after the first Mortal Instruments film, starring Lily Collins and Jamie Campbell …

-

Tis’ the Season — For Great Fall Picture Books!

With summer behind us and another school year underway, now’s a great time to look ahead and see what new picture books are about to hit our shelves. While there …

-

Susan Cain, Acclaimed, New York Times Bestselling Author of Quiet, to Publish New Edition for Children

New York, NY — International bestselling author and co-founder of Quiet Revolution, Susan Cain will publish QUIET POWER: The Secret Strengths of Introverts in May 2015 with Dial Books for Young Readers, an …

-

Candlewick Press Books on Permanent Display at NYPL Shop

October 9, 2014 – Candlewick Press announced today that select titles will be on display and available for sale at the Readers & Writers Shop in The New York Public Library. The collection, …

-

Bibliophiles Around the World Return to Slow Reading

Some enthusiasts claim that slow readers should exclusively use print books. Others do not feel that such a limitation is necessary. For those who choose to use a mobile device, …

-

Chris Van Allsburg Hopes to Inspire Kids to Be Great Pet Owners

The story follows a hamster’s transition from living in a pet store to moving in with a family. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Books for Young Readers will publish The Misadventures of …