Month: May 2015

-

Tuck Everlasting Musical to Debut On Broadway in 2016

The Broadway-bound musical — about love, family and living life to the fullest — features a book by Claudia Shear, music by Chris Miller and lyrics by Nathan Tysen. It …

-

The CBC and the unPrison Project's Prison Nursery Libraries Initiative Featured on MSNBC

In honor of Mother’s Day and the 96th annual Children’s Book Week, the Children’s Book Council partnered with the unPrison Project to establish prison-nursery libraries in 10 states. Jiang-Stein spoke …

-

What Are You?

A Post That Has Nothing to Do with Sookie Stackhouse

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Christian Trimmer

“What are you?”

“Uh…”

“I mean, where are you from?”

“Oh! Chicago.”

“No, where are you from from?”

“America?”Throughout my life, I’ve had conversations like the above. It’s human nature to put people into categories, and I was not easily placed. I inherited my Vietnamese mother’s eyes and cheekbones and my white father’s nose and skin tone, giving me what has been called an “exotic” look.

From an early age, I made efforts to define my racial identity (something kids do as early as two years old, for themselves and others, according to a number of studies). As a boy, I identified as white. Other than my mom, who was the only one in her family to move to the United States, all of my relatives were white. The neighborhood I lived in was predominantly white. Plus, everyone on the TV shows I watched and in the books I read were white (or animals). On top of that, when I went to Little Saigon in Chicago with my mom, I felt distinctly “other.” It’s not surprising that I would choose to identify with my white half. Dr. Erin Winkler, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin, notes, “[C]hildren pick up on the ways in which whiteness is normalized and privileged in U.S. society…picture books, children’s movies, television, and children’s songs…all include subtle messages that whiteness is preferable.”

But my classmates had different ideas. My eyes were slanted enough to earn me the label “Chinese” (it was the 1980s—everyone Asian was Chinese). I excelled at school, particularly in math, and was an accomplished tennis player (a sport that requires focus and discipline), only because, as my peers regularly informed me, I was Asian.

Throughout high school, I continued to try to downplay my Vietnamese heritage—I wanted to be like the cool, popular white kids around me. When I got to college, though, I started to self-identify as Asian (I’ll tell you why over a drink). Mind you, I didn’t join any of the Asian-American groups on campus; I simply started saying “I’m Asian” when asked “What are you?” After moving to Los Angeles, I switched back to white (I’ll tell you why over a drink). My commercial agent thought differently, sending me to castings where I was alternately the whitest, most Asian, or least Hispanic person there.

It’s only within the last decade that I’ve embraced both sides of my heritage. (The opportunity to choose one’s own racial identity is a relatively new one.) It’s important to me that I honor my mom and dad’s influences on me, so I make a point to correct people if they place me in just one category. For a while, I used the word “Eurasian.” Now, I describe myself as biracial and give the specifics if asked.

I’ve chatted with friends who are biracial or multiracial, and we’ve all had very different experiences, depending on our mix, gender, and geography. One thing we have in common is that none of us could single out a book from our childhoods that captured the experience of being multiracial. Where were the books for us? Don’t “exotic” people deserve to have their stories told, too?

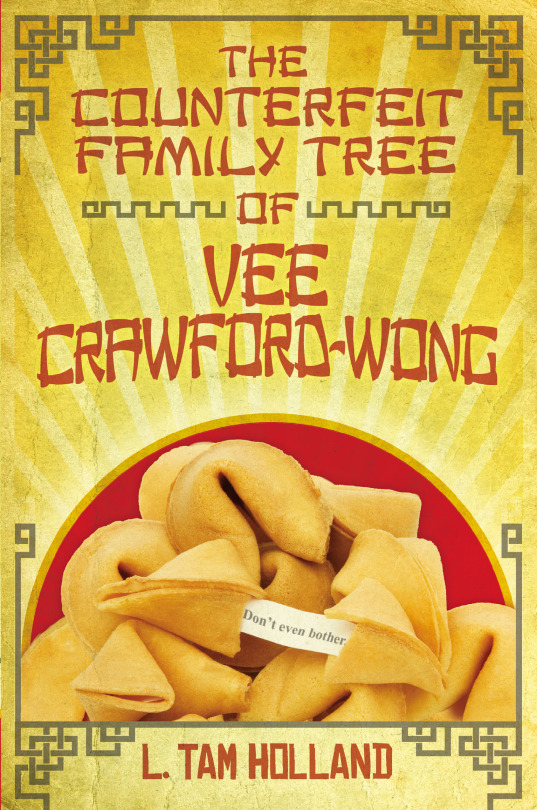

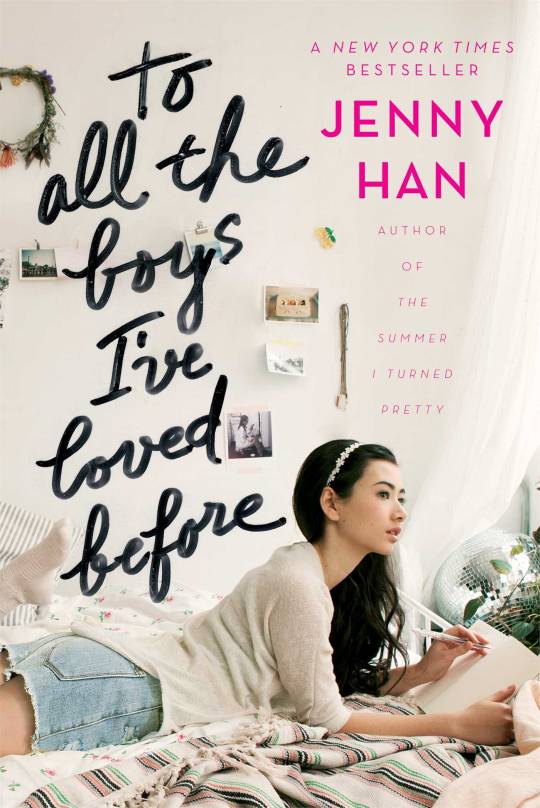

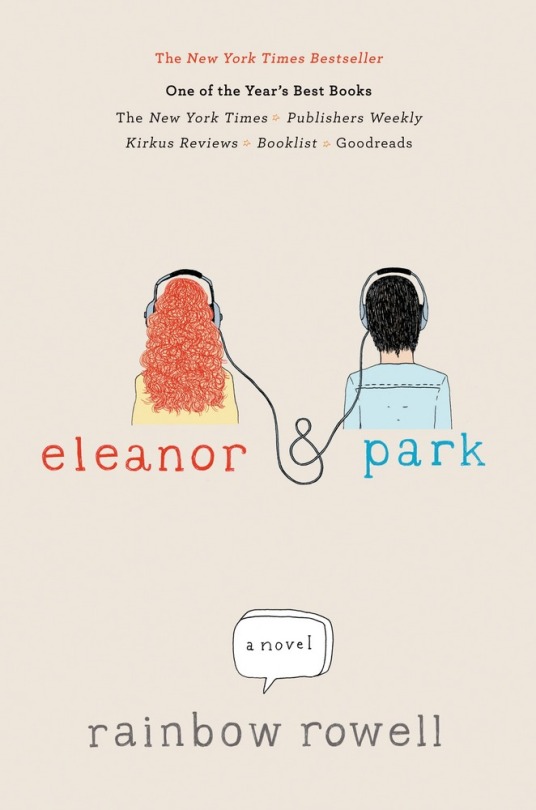

Happily, today there are a number of children’s books that are about or star kids who are mixed. (Do a search on Goodreads and you’ll find lists for all reading levels.) I’ve had the pleasure of reading novels that have characters whose upbringings mirror my own, books like The Counterfeit Family Tree of Vee Crawford-Wong by Lindsay Tam Holland, To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han and Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell. I saw myself in Vee, Lara Jean, and Park’s stories. I would have loved to have read them as a teenager.

With nine million Americans identifying as more than one race, with one in every seven marriages being between spouses of a different race or ethnicity, and with the number of mixed-race babies soaring, the demand for more of these stories is growing.

As an editor, I’m looking to acquire projects that address the biracial experience. As a writer, I hope someday soon to add to the canon of existing titles.

Christian Trimmer is an executive editor for Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers. He is also the author of the picture book Simon’s New Bed, out 8/25/15. Learn more at christiantrimmer.com.

-

Little Free Library® Announces Worldwide Book Drive for Children's and Young Adult Books At Its 25,000 Locations

Minneapolis, MN — To mark its third anniversary as a non-profit organization on Saturday, May 16, 2015, Little Free Library® invites the public to participate in the Worldwide Little Free Library Book Drive by donating new …

-

Turning Prisons into Reading Centers

Every child in the world deserves reading and literacy, not just those whose parents live in the free world.

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Deborah Jiang-Stein

At a time when most babies coo along with lullaby wind-up toys, my ambient sounds were women’s voices in small clusters and the wail of a siren across the prison compound for count time. Count is when prisoners report to their bunks in their cells or living units while the guards count the population. Three times a day for a year, the siren blasted in my backyard—the prison yard.

I was born in prison during the beginning of one of my birth mother’s many prison sentences. She was a heroin addict sentenced for drug-related crimes, much like many in prison today. She was in the first months of pregnancy at the time of her sentence, and I lived in the prison for a year until Child Protection Services removed me for placement into foster care. Later, I was adopted into a family of academics, my parents both English teachers.

But sometimes I’ve wondered: Did anyone read to me in prison? Was my birth mother allowed board books in the room I shared with her for the year we spent together?

Whether she did or didn’t, I’ll never know. What I do know is that my love of learning, one reason why I am a writer today, is because the family who adopted me instilled a love of words and reading within me, along with a passion for art, music, theater, and dance — all things creative.

My exposure to reading as a child led me to found The unPrison Project because:

1. I have a deep-rooted tie to women in prisons, especially mothers.

But most of all because the facts prove what I’ve known all along:

2. Life skills like reading and literacy, and non-cognitive skills like persistence, goals planning, and self-confidences, all contribute to success in our communities.

I also founded The unPrison Project because:

- Two thirds of women in prisons are mothers, the majority with young children under age 10.

- 7-10% of women sentenced to prison are pregnant at time of sentencing.

- Most often, infants are removed at birth and if arrangements aren’t made with a family member for custody so the baby enters the foster care system. Thus begins a second generation of trauma due to mother-child separation.

The science of early childhood development teaches us that a child acquires the ability to think, speak, learn, and reason during his or her first three years of life. A baby’s early experiences shape his or her brain’s architecture, building either a strong or a fragile foundation for life, learning, and health. Adverse early experiences and deprivation can impact a baby’s brain development for an entire lifetime, and positive learning experiences can set the path for self-esteem and possibility.

After years of speaking in prisons to talk about the value of life skills, I recognized the void of children’s books in visiting rooms as well as in the prison nurseries where I visited mother-baby programs.

Nine states (New York, Washington, West Virginia, California, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Nebraska, South Dakota) currently have on-site nurseries for a select number of pregnant inmate mothers to live with and care for their babies born during their prison sentence, and another nursery is scheduled to open in the Wyoming women’s prison in the near future. Often, local community agencies will donate nursery supplies, clothes, cribs, and other material needs, but there’s always a need for new and current diverse books.

Many prisons say they only have “only a few dog-eared books” in their visiting rooms. Visiting rooms in prisons, as well as in juvenile detentions, are the equivalent to one of the largest “in the margins” classrooms. These spaces are ripe for the development of on-site children’s book library carts and reading centers for learning and literacy.

By stocking prison nurseries with inclusive children’s books for ages 0-3, babies born in prison are groomed for a lifelong love of reading and learning.

Literacy is learned, and parents who can’t read or write often pass on illiteracy.

A partnership between the Children’s Book Council and The unPrison Project is providing an abundance of new books for prison nurseries, and also for visiting rooms in prisons. Our goal is to help set the groundwork for literacy in the next generation and, at the same time, nurture new bonding and parenting skills for incarcerated mothers, which is as important inside prison as it is outside.

This specific and large diverse market of incarcerated mothers and their children need attention. What if prison nurseries and visiting rooms were turned into reading centers? Providing an environment of reading and literacy will help change the prospects of babies born to mothers in prisons. As the late Walter Dean Myers said, “What I believe is that we need to have every child reading to give them a shot at life.”

The CBC/unPrison Project partnership makes a statement that reading is for every child, not just those with parents in the free world. The CBC/unPrison Project partnership makes a statement that reading is for every child, not just those with parents in the free world.

Reading creates an altered state, a grounding between parent and child. If it weren’t for my early exposure to reading and the exploration I’ve found in words and books, I most likely would have continued to follow in the footsteps of my birth mother. Instead, I’ve made my mission to give back in whatever ways I can to the communities of my roots, those inside prisons.

Our world will be a better place when we each find ways to give service to others and, for me, I can’t imagine a better way than to open up a world of possibilities through stories.

Deborah Jiang-Stein, author of the memoir, Prison Baby, is a national speaker and founder of The unPrison Project, a 501c3 nonprofit working to empower and inspire incarcerated women and girls with programs, resources, and tools for life skills and mentoring. For more than 10 years, Deborah has championed support for people in need of freedom, education, shelter, and job development.

- Two thirds of women in prisons are mothers, the majority with young children under age 10.

-

Marcia Brown Has Passed On

“Ms. Brown was one of only two artists — the other is David Wiesner — to receive the Caldecott Medal three times. She also illustrated six Caldecott Honor Books, as the runners-up are …

-

Watch the Red Carpet Interviews from the Children's Choice Book Awards!

Meet the 8th annual Children’s Choice Book Awards winners at CNN.com!

-

First Book's Stories For All Project™ Arms Educators With Diverse, Inclusive Children's Books to Fuel Learning, Promote Educational Equity

WASHINGTON, D.C. – Educational outcomes improve when children have access to books in which they see their lives reflected. They become more engaged and enthusiastic readers, a critical step to succeeding …

-

Children's Book Week 2015 #storylines: Laurie Ann Thompson

Our final quote is by Ghanaian athlete and activist Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah, via Laurie Ann Thompson’s picture-book biography, Emmanuel’s Dream (Schwartz & Wade/Random House Children’s Books, 2015): See other quotes …

-

Children's Book Week 2015 #storylines: Ellen Oh

Celebrate what makes you one-of-a-kind with this quote from Ellen Oh’s The Prophecy (HarperCollins, 2013): See other quotes in the series, and share your favorites! Quote #1: Frances Hodgson Burnett, …

-

Children's Book Week 2015 #storylines: Kwame Alexander

Encouraging words from Newbery Winner Kwame Alexander’s The Crossover (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014): See other quotes in the series, and share your favorites! Quote #1: Frances Hodgson Burnett, A Little …

-

2015 Comstock and Wanda Gág Read Aloud Book Award Winners Announced

Eighteen regional teachers and librarians, along with Minnesota State University Moorhead students read aloud 286 picture books to 21,988 children during the year. The winners and honor books were selected …

-

CBLDF’s Comics Connector Builds A Bridge Between Libraries, Educators, and Comics Creators!

For Immediate ReleaseContact: Charles.Brownstein@cbldf.org Comic Book Legal Defense Fund continues the celebration of Children’s Book Week by launching its newest resource – the Comics Connector! CBLDF’s Comics Connector is a directory resource that connects educators and librarians with creators, …

-

News-O-Matic Daily News App Is Just for Kids

News-O-Matic inspires children to be engaged and informed citizens. Readers can discover ways to take action within their community, or share their thoughts and questions with a worldwide network of …

-

Children's Book Week 2015 #storylines: Leila Sales

Take pride in your individuality with this line from Leila Sales’ heart-pounding YA novel This Song Will Save Your Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux/Macmillan Children’s, 2013): See other quotes in …

-

Get Caught Reading Comic Books, Challenged Books and Other Must Reads

WASHINGTON, D.C. — What do Archie, Fone Bone, Hip Hop Family Tree, Usagi Yojimbo and the Peanuts gang have in common? These comic book icons have all been “caught reading.” This …

-

Mirrors and Windows

Contributed to CBC Diversity by Delia Sherman

It’s 1961. I’m 10, and in bed reading a book. My mother isn’t telling me to go outside and play because, first, we live on the 11th floor in an apartment building in New York City, and second, because playing outside always makes me wheeze.

The book I’m reading could be anything—though, if I’m really sick, it’s likely to be The Swiss Family Robinson. The Swiss Family is mostly male and much older than I, but the practical details of their island life and the girl who has built her own house all by herself are endlessly fascinating to me.

This is my special comfort book, but I also love The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood and the Narnia series and the biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine from Mama’s nightstand, The Wind in the Willows, Nancy Drew, and A Wrinkle in Time. As an adopted only child, I find books about big, warm families of colorful siblings exotic and fascinating. But I like Little Men even more than Little Women. The boys of Plumfield School feel like a family even though they aren’t related by blood. I particularly identify with the musician Nathaniel, who is delicate and sensitive and lies a lot.

I’m a girl and I can’t read music, but I understand why he lies. I lie to stay out of trouble, too.

Some books act as mirrors—reflecting the reader’s experience—and some as windows—inviting readers to empathize with characters who may not look like them or think like them or share their beliefs or tastes.

Realistic novels of domestic life are the most obvious mirrors, but fantasies and historical fiction can be mirrors, too, and allow readers to see characters like themselves in the center of the action, solving problems, struggling against adversity, making decisions, and earning their happy ending—or tragically failing, but still being important, and above all, familiar. Window books are seldom comfortable or soothing, but they help us understand that, while we are not all the same, we are all human, with stories worth hearing.

Mirror or window is not an absolute state. A book like Virginia Hamilton’s Justice and Her Brothers is a mirror for some readers, a window for others. It is true, however, that most novels tend to reflect the dominant culture. In countries whose population is racially diverse and culturally heterogeneous this creates a terrible imbalance.

In the United States, there are plenty of mirror books written for male, educated, heterosexual, able middle class White Anglophone Christians. Women, LGBT people, people of color or different religions or languages or cultures or abilities are frequently pushed into the margins, cast in supporting roles, treated as exotic, dangerous, or inferior, misrepresented, or just left out completely. The books that mirror their lives and experiences are often assumed to be more formulaic, less interesting, less relevant, less important.

It’s the 21st Century now, and I’ve left my isolation behind in the 20th, along with my asthma. I write books as well as read them, and my stories mirror the things I’ve experienced and observed. My childhood in one of the most diverse and heterogeneous cities in the world is reflected in my two New York Between novels, Changeling and The Magic Mirror of the Mermaid Queen, set in a magical New York peopled by supernatural immigrants to the New World. The Freedom Maze, about a 1960’s white girl who goes back in time to her family’s plantation in 1860 and is taken for a light-skinned slave, is part of my lifelong struggle to understand and overcome the unthinking racism I grew up with.

Most of my stories contain characters of many colors, genders, ages, and sexual orientations because they are part of history—even Western European history. They show up in diaries, memoirs, census lists, cemeteries, and local records of all descriptions. Mirroring their experience opens a new window on our shared history, both good and bad.

The truth is, every reader needs both kinds of books. All children—all adults—need positive, undistorted images of their own reality. They also need positive, undistorted images of the reality of the other.

Diversity is a fact. Books that don’t acknowledge it are not mirrors, but shuttered windows. In the real world, skin color, gender, physical ability, sexual orientation, or even religion and class, in no way limit intelligence, competence, leadership ability, or common sense—although studies suggest that marginalized people tend to be more empathetic and generous, perhaps because they encounter so many window books.

No matter what we look like, no matter what we believe, we are all human. The best way to understand that—to develop empathy—is to read each other’s stories.

Delia Sherman was born in Japan and raised in New York City but spent vacations with relatives in Texas, Louisiana, and South Carolina. Her work has appeared most recently in the young adult anthologies The Beastly Bride: Tales of the Animal People; Steampunk! An Anthology of Fantastically Rich and Strange Stories; and Teeth: Vampire Tales. Her novels for younger readers include Changeling and The Magic Mirror of the Mermaid Queen. She lives in New York City.

-

Children's Book Week 2015 #storylines: Cynthia Leitich Smith

A powerful lesson in love from Cynthia Leitich Smith’s Eternal (Candlewick Press, 2009): See other quotes in the series, and share your favorites! Quote #1: Frances Hodgson Burnett, A Little …

-

Starting a Conversation with Young Readers

The tips are for sparking discussion with young readers of all ages, from toddlers to teens. Suggestions include incorporating the story into playtime; asking personalized questions; and making real-world connections …

-

Asbury Park School District Invests in Literacy for All

Asbury Park, NJ – As part of Superintendent Dr. Lamont Repollet’s ongoing efforts to raise achievement for all students in the Asbury Park School District, the Board of Education has …