Blog

-

Candlewick Press Announces Publication of New Book by Newbery and Caldecott Award–Winning Team Laura Amy Schlitz and Brian Floca

SOMERVILLE, MA – Leading independent children’s book publisher Candlewick Press is announcing the publication ofPrincess Cora and the Crocodile , a gorgeous and original storybook collaboration from Newbery Award–winning author …

-

Roald Dahl’s 100th Birthday Celebration

The celebration will include new editions of Dahl classics featuring Quentin Blake’s illustrations; the Splendiferous Showdown, a touring trivia show starring the Story Pirates; community celebrations across the country; and much …

-

New Report from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Reveals Educators Hungry for Professional Learning and Greater Family Engagement

BOSTON, MA – Global learning company Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH) today announced the findings of the second annual Educator Confidence Report, which examines educator sentiment on a range of issues, …

-

Morton Schindel, Founder of Weston Woods Studios, Dies at Age 98

New York, NY – Morton Schindel, founder of Weston Woods Studios, the leading provider of audiovisual materials adapted from award-winning children’s books, died peacefully Saturday, August 20, 2016 at age …

-

The Evolution of Children’s Literature

According to Lerer, children’s books originated in the 1740s and were written to instill moral behavior. The alleged Golden Age of children’s literature that extended from the Victorian era until the Second World …

-

DOGObooks and YALSA Partner for 2016 Teens’ Top Ten voting

CHICAGO, IL – Today the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) announced that DOGObooks, the largest website for kids and teens to review books, will host the voting for the …

-

The Force of Reading Awakens This October 2016 for ‘Star Wars™ Reads’

GLENDALE, CA – Disney Publishing Worldwide and Lucasfilm Ltd. announced today that Star Wars Reads will return for its fifth year this October to celebrate reading with Star Wars-themed events around …

-

Scholastic and ASCD Launch 3-Day Professional Learning Institute for Educators Focused on District-Wide Literacy Improvement

Literacy Leaders’ Institute Brings Together Practitioners and Thought Leaders Kylene Beers, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, Cindy Marten, Ernest Morrell, Robert Probst, Among Others, to Explore How to Implement Comprehensive Literacy …

-

Gallery Books and Aladdin to Publish Books by Maddie Ziegler

NEW YORK, NY – Gallery Books and Aladdin, an imprint of Simon & Schuster’s Children’s Publishing, will publish multiple books by 13-year-old award winning professional dancer and actress Maddie Ziegler, it was announced …

-

Where’s Your Power?

Contributed by Sharon Mentyka, Writer

I belong to the most privileged group in our culture: white, heterosexual, and able-bodied. And although my female gender brings me down a notch or two, my race membership alone gives me a winning lottery ticket in life.

So when I began to write books for children in earnest, one piece of advice from an instructor in my MFA program seemed to suit me. “People will tell you to only write about what you know,” she said. “Don’t listen to them. Instead, write about the things you want to learn.” There was so much I wanted to learn. And the stories I yearned to write begged for research, listening, and learning.

Then I made a mistake. One that would have perpetuated a racist stereotype had I not been saved by a sensitivity reader.

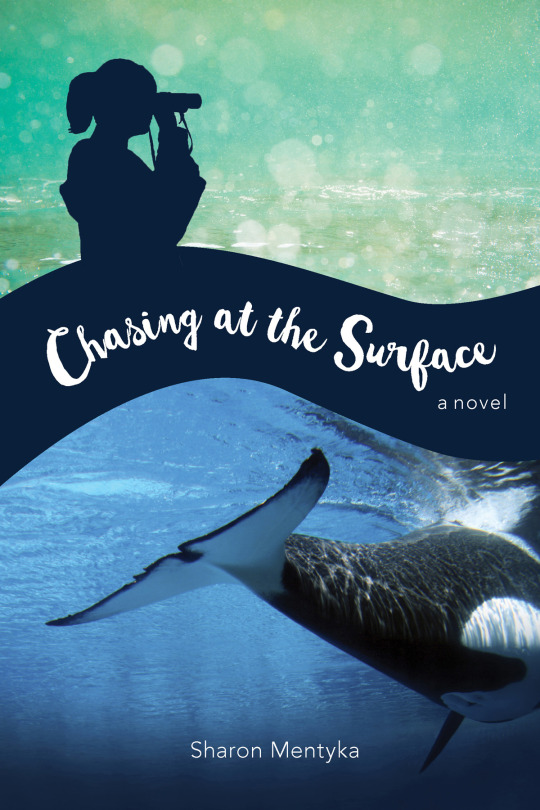

My forthcoming middle-grade novel, “Chasing at the Surface,” set in the Pacific Northwest, tells the story of a 12-year old girl whose mother mysteriously leaves home just as a pod of orca whales become trapped in an enclosed inlet. The setting for the book borders the ancestral lands of the Suquamish Tribe, who have lived in Central Puget Sound, across from present-day Seattle, for approximately 10,000 years. Like many Coast Salish people, orca whales are central to their stories, art and culture. Early on, I made numerous contacts with tribal members, checking facts, word translations, traditions and references—the hard facts that I hoped to include in my book.

Yet my characterization of one young Suquamish veered dangerously into stereotype when I singled him out as the only one struggling with domestic issues, self-esteem and alienation from his own culture, and turning to white culture to be “saved.” In fact, as I later learned, the Suquamish put the majority of their resources towards caring for their children and elders. They are the Tribe’s top priority and the situation I had blindly presented in my initial draft would never have been allowed to happen.

The experience froze my liberal white heart. How was it possible that, despite best intentions, I made a blunder that would have ended up hurting the very readers I had set out to serve?

The answer is easy; Best intentions mean nothing.

Intentions are conscious. My biases were unconscious, born out of my frame of reference as a white person of privilege. Because really, we’re not aware of walking until we put on a pair of too-tight shoes. I had become so accustomed to the inherent ”truth” of these deep-rooted stereotypes, activated and reinforced by social mores and media, that I completely failed to notice what was glaringly apparent and offensive to a member of a marginalized community and to me once it was pointed out to my conscious mind.

But failure to notice privilege does not diminish its effects.

Let me be clear here. Many who embody the definition of privilege do not yet acknowledge the power of their position, either through inattention, fatigue, or disbelief. We know that publishing is overwhelmingly white, with an industry-wide average of 79%. Yet we are all still making unimaginable mistakes.

Because of inherent biases, editors either don’t notice or overlook language in titles or illustrations that reference myths and metaphors that hold strong negative meanings to marginalized communities. Books that give a false representation of the brutal history of slavery continue to be published to starred reviews. Stories with protagonists of color still emerge with their covers whitewashed. Without a concerted effort to take notice, to train our conscious awareness of how our inherent biases affect our understanding, actions, and decisions, we will always operate out of this position of privilege to the detriment of those with less power.

So what is the way forward when the problem seems to exist at every step of the way, from manuscript idea, to writer, to agent, to editor, to publisher, illustrator, promoter, reviewer, and librarian? You’re trying to do the right thing, but it seems as if no matter what you do, it’s always wrong. It feels so unfair.

Good. This is how it should be.

For too long, those of us in positions of privilege have been far too comfortable. If there is any chance of affecting real change, shifting the paradigm, we need to be okay with feeling uncomfortable, okay with having every action we take watched and evaluated. We all know there are more books about animals than there are about children of color. If diversity is going to be more than just an industry buzzword, each of us needs to find our own power to give to the cause. Each of us who occupies a position of privilege needs to make our own decisions on where we stand, how uncomfortable we are willing to be, how we will make sure that the stories we tell are told sensitively and from a place of truth.

So where is your power? Are you a reviewer who can look beyond author and publisher marketing and evaluate books for explicit and implicit racism? Are you a librarian who can push your supervisors to shelf books by or about people of color in the “Fiction” section rather than “Multicultural Fiction?” Are you a marketing exec who can help counter the mistaken notion that the only audience out there worth marketing to is a white audience?

And writers? Seeing the world through someone else’s eyes is a challenge. But isn’t that what writers do, as we examine our own racial experiences as both a mirror to ourselves and a window to the world around us? Yes, it’s a fine balance. But it’s not a good enough reason for not making the attempt, which only perpetuates what the writer and journalist Nisi Shawl calls, “the greater failure of exclusion.”

Sharon Mentyka is a writer and teacher in Seattle with an MFA from the Whidbey Writers Workshop. Her stories and essays for both children and adults have appeared in numerous literary magazines. B in the World, an illustrated children’s chapter book about a gender non-conforming child was published in 2014. Chasing at the Surface, her debut novel for middle grade readers, inspired by an actual visit of orca whales to an enclosed inlet in the Pacific Northwest, will be published by WestWinds Press in October. SharonMentyka.com

-

Pottermore to Publish Pottermore Presents 6 September, A Series of eBook Shorts About the Wizarding World from J.K. Rowling

London, England, 17 August, 2016 – Susan L. Jurevics, Chief Executive Officer, Pottermore, announced today the publication of Pottermore Presents, a series of eBook shorts featuring stories and J.K. Rowling’s …

-

CliffsNotes® Gets Personal; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt and BenchPrep Partner on Digital Learning Solutions for High School and College Students

BOSTON, MA – Global learning company Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH) and BenchPrep, a digital learning platform company, today announced the availability of new personalized digital learning solutions for the iconic …

-

Global Tour to Continue For Release of Book 11, Diary of a Wimpy Kid: Double Down

NEW YORK, NY — Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS, today announced both the international countries and domestic US cities for bestselling author Jeff Kinney’s continuing global author tour. Promoting …

-

Vote for the 2016 Teens’ Top Ten!

Visit DOGObooks.com to vote! You can check out previous years’ winners here.

-

The Reading Without Walls Podcast: National Ambassador Gene Luen Yang at Comic-Con 2016

Through his platform, “Reading Without Walls,” Yang hopes to inspire readers of all ages to pick up a book outside their comfort zone. In episode five of his podcast, Yang …

-

Scholastic Announces Sales of More Than 3.3 Million Copies of ‘Harry Potter and The Cursed Child’ Parts One and Two

New York, NY — Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Parts One and Two script book, the eighth Harry Potter story by J.K. Rowling, John Tiffany, and Jack Thorne, published …

-

National Ambassador Gene Luen Yang at San Diego Comic-Con 2016

Yang appeared on panels with fellow comic book creators Emily Carroll (Through the Woods), John Patrick Green (Hippoptamister), Noelle Stevenson (Nimona), and more throughout the event. Check out more photos from the convention …

-

Six Flags New England Hosts the First-Ever “Read a Book Day”

What: On Saturday, August 27, Six Flags New England and Candlewick Press are celebrating literacy with their first-ever “Read a Book Day.” The Coaster Capital of New England and Candlewick …

-

Christian Robinson to Illustrate 2017 Children’s Book Week Poster

New York, NY — August 11, 2016 — Acclaimed illustrator Christian Robinson has agreed to design the 2017 Children’s Book Week poster distributed by Every Child a Reader and the Children’s Book …

-

ALSC Now Accepting Applications For 2017 Penguin Random House Young Readers Group Award

CHICAGO, IL — The Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC) and the Grants Administration Committee are now accepting online applications for the 2017 Penguin Random House Young Readers Group …